The magic measure is a complicated code that pivots people’s psyche

The truth shall set you free; but first, it makes you angry. Repeatedly, investors are fed this baloney that the equity market index is a barometer of the economic health of a country. There can be no greater lie than the revelation that the small basket stock index – such as the Sensex in India, the Dow Jones Industrial Average in the US and the FTSE in UK et al – measures the economic health of the respective nations.

Followers of this flawed logic say that since the Dow is an international aggregator (accounting for a quarter of the global GDP), the Sensex might as well chase the global guesstimate besides worrying about ‘I’ in the BRIC world. If the Dow drops, the Sensex along with Nikkei, Hang Seng and Kospi et al must also fall; if the Dow jumps, the Sensex and others must dutifully rise. And they hawk investment strategies based on this crooked correlation. The reality is as far from the stupid assumption as the two trading rings themselves separated by continents, mountains and oceans in between; not to forget the governments, armies, respective laws of the land, practices of the people as well as the number of investors and the size of their bank accounts.

It is just impossible for any statistician to find out and tell how many index points equals to how much dollars worth of the market capitalisation and, that in turn, corresponds to how much of the reported economic output.

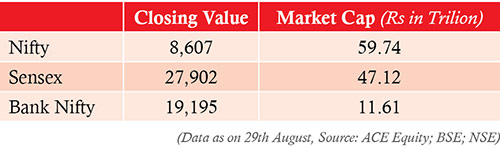

Equally eccentric is the situation, if the theory were to hold true, with India’s Nifty having a market-cap of Rs 59.74 tn, 27 per cent higher than that of the Sensex at Rs 47.12 tn, but the index valued at 8,607 which is just 30 per cent of the Sensex (27902). More madness in the assumption is seen in the Bank Nifty, constituted of twelve banks reads a number of 19,195, more than twice that of the broader Nifty, but has a market-cap of Rs 11.61 tn. Anything is possible in politics and stock markets.

Any stock index anywhere in the world, after millions of computer calculations performed moment-by-moment, is just a temporary extract number. Nothing more than that! Nada! This magical and momentary number has no tangible real relationship with another misleading number that goes by the acronym GDP.

The core of the problem lies in the fact that the core of this complicated code – the capitalisation method to calculate this puzzling cipher – is illusory. It is made up of momentary stock prices that in turn are made up by men’s mind and determined by various factors, many of which are predominantly psychological in nature. Stock prices are indeed determined not by the fundamental factors alone.

The stock exchange authorities that own, update and disseminate the stock index numbers compute it every few seconds. The value of the index is calculated and disseminated automatically, on a real time basis, considering the prices at which the trades in the index constituents are executed. The inputs that they use to figure out and flash this number are stock prices of a select basket of companies and not the output by factories and farms. It is just impossible, even for the most super computers, to first collect, collate and then compute the data on physical economic output worth trillions of dollars of such a vast nation in a tiny eye-blinking time period. Secondly, they calculate the index, moment by moment, only during the market trading hours on weekdays and stop doing so once the video game shuts shop for that day and also do not do the math on holidays, which total about 115 days or full one-third of the year.

Does it mean that the economy shuts and stops producing steel, cement, petroleum, power, medicines, computer chips, gunpowder, shoes, textiles, garments and milk, etc., the moment the roulette ring stops and the glittering game show comes to an end? Anyone with a little common sense would not accept the same. The contribution to the GDP by entrepreneurs who set up enterprises that work 24×7×365 and a farm labour who works from dawn to dusk may be admirable and may also be measured accurately by their respective owners, besides government accountants for the purpose of tax, whether the Sensex senses and the Dow heeds it or not.

Politicians and their followers in the ring have vested interest in feeding this grand poppycock. They have to parrot what sounds music to their political masters and truly believe in the principle “do-as-directed.” The rise and fall of the index has nothing to do with the economy or with anything that the politicians are doing. In fact, most often, what they do is exactly the opposite of what they should and ought to be doing. But then, it is a known fact that the nation’s economic interests, private business groups’ agenda, individual minister’s personal ambitions and the ruling party’s objectives all are seldom congruous.

When the radio and television networks say “the market is up (or down)”, they commonly refer to the Dow, Sensex or the Nifty’s movement on that day. The imagination, then cleverly repeated by talking heads is further stretched to extend to the economy and the country’s progress as a whole. General masses – drivers, security guards, vegetable vendors, couriers, factory workers, sales persons, tailors, carpenters – hardly care whether GM stands, or may be, sits, for General Motors or Government Motors, whether it sells cars or is itself up for sale and whether it is running up or down the ticker. The electronic media seems more concerned to know which way the index and the bets are moving.

The ideal index is intended to instantaneously give readings about how the stock market perceives the future of the corporate sector, which in effect means how the market is speculating on the expected share prices. Even the current price of a stock at a given moment is a potent influence in fixing its subsequent market value. As the index itself is influenced by the expectations about future performance of stock prices, it leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When a herd of investors, inspired by the news of the day, think that the stocks are going to go down, everyone would want to sell, in effect dragging stock prices and bringing down the index as well. The stock index can often act as a trigger to incite this herd behaviour. The downturn influences the traders’ collective psyche which would further accelerate the fall, thus setting off a system-wide disperse “stop loss” orders as investors rush to protect their portfolios, further depressing the market. Technical oriented traders generate a wave of ‘‘buy or sell orders’’ depending on certain ‘critical psychological’ levels of the index. The gauge touted to be investors’ popular guide pivots their perceptions and bamboozles rather than enlighten them.

Stock prices are influenced by the perceptions of various types of market participants – die-hard buy-and-hold disciples, momentum and technical traders, intra-day wagers, large institutions playing on someone else’s money and corporates, company promoters and insiders. These flickering prices are captured to compute the index number that in turn sways the traders’ perceptions, who then adjust their bets and change the invitation price they are willing to pay or take in order to buy or sell a stock. And the roulette wheel keeps moving on, and on, and on.

The notion that the stock index is an economic barometer assumes that since stock prices follow corporate performance, which in turn is reflected in the GDP, the index derived from those stock prices and the GDP are closely correlated. Long term historical data from across several countries shatters this assumption and proves that there is no correlation between the market index movement and the countries’ GDP.

The theory fails to explain the ‘flash-crashes.’ There have been several instances when the index has dropped 20 percent or more on a single day, forcing market closure and evaporating trillions of dollars from market capitalization and investors’ wealth. In none of these occasions did the country’s GDP fall by an equivalent, or a factor, of that amount nor was there a threat that it would do so the next day when the government accountants calculate the figures. When the Sensex hit an upper circuit of 20 per cent on May 18, 2009 forcing market closure for the day, barely seconds after the opening bell, the country’s GDP did not gallop by that amount in a single day, nor did the thirty companies, all in a day, said that their profits would rocket in the next reporting quarter.

What propelled the index on the day was the poll result which declared victory for the Congress party led coalition to form the next government. It was a political event that changed investors’ perceptions; not a scientific invention or a great discovery that would change the macro and micro economic situation overnight.

It’s not only a plain misnomer, but a deceptive delusion that the equity index is an economic barometer. It’s just a flashing abstraction that the traders take as a pivot, and get pivoted, for placing bets on individual stocks. It’s not without a reason that the index components are called pivotals colloquially.

Thirty spokes share the wheel’s hub; It is the

center hole that makes it useful

– Lao Tsu; Chapter Eleven, Tao TeChing