I remember nothing of my first trip to Paris. The year, 1939. I was two, Elinor, my sister, five. Mother was in Norway on a lecture tour, her return to France made difficult by German U-boats in the Baltic. Luise, the young woman caring for us, took us to Le Harve to board the Normandie on what proved to be its last voyage from Europe to the United States. From the deck of the ship, Luise spotted her French army boy friend on the dock. She thrust me in the arms of a woman standing nearby and rushed down the gangplank to embrace Henri one last time. The woman was the eminent actress, Helen Hayes. Decades later, at a theater benefit, I found myself standing next to Miss Hayes. Why, oh why, did I fail to ask, “Do you remember me?”

On my present trip to Paris, I am staying at a lovely Left Bank hotel, the Hotel de Seine. A block or so away is the Rue des Beaux-Arts. In 1970, I stayed on this street at the Hotel de Nice, now no more. After a long day walking on the streets of Paris, I return to the Hotel de Nice. The woman at the front desk is in tears. She tells me that General de Gaulle has died. I, too, feel tearful. Such a great man. Twice savior of his country : As leader of the French during World War II and ending the Algerian conflict tearing France apart.

“Le general de Gaulle est mort; la France est veuve.”

“General de Gaulle is dead. France is a widow.”

(President Georges Pompidou) The novelist and Minister of Cultural Affairs, Andre Malraux: “A man of the day before yesterday and the day after tomorrow.” (My interpretation of Malraux’s comment : de Gaulle, both guardian of the nation’s history and visionary.)

Also on the Rue des Beaux-Arts is L’Hotel, now an elegant place, but not so in 1900 when Oscar Wilde died there at age 46. Five years earlier, a jury in England had found Wilde guilty of indecent acts. The trial judge sentenced him to two years at hard labor. On the day of his release from Reading Gaol, he left England for France on the Channel boat, never to return. He began his “Leftover Years” of exile, the moving term of his biographer, Richard Ellmann, for the remaining 3 1/2 years of his life, separated from his wife and two sons, shunned and impecunious.

Soon after his release from prison, Wilde started his last literary work, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol.” When published, the author of the poem was identified not by his name, only as “C.3.3”, the number of Wilde’s prison cell :

I never saw sad men who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

We prisoners called the sky,

And at every happy cloud that passed

In such strange freedom by.

Wilde is buried at Pere-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His monument bears these lines from the poem :

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

I am in Paris for ten days. Most mornings I start the day by writing in the Luxembourg Gardens, a short lovely walk from my hotel. I sit on a green metal chair by the sailboat pond and gaze at the palace. There is something about this place that stirs my creative juices. (The same with Venice.) After writing, I walk to the basketball court. Odd that shooting baskets in the Luxembourg Gardens makes me feel “Parisian.”

A short walk from my hotel in the other direction brings me to the Seine and Pont des Arts with its wooden plank walkway. I gaze upon the glorious Institut de France, a 17th century architectural masterpiece, home of the French Academy, guardians of the French language. From here I look at the Pont Neuf — the “new bridge” — a building project of King Henry IV who ruled from 1589 to 1610.

Henry is my favorite French king. When I inquire of Parisians who is theirs, I receive puzzled looks, so I explain why he is mine. Henry was a man of tolerance living in intolerant times. The times : In Paris, the St.Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Huguenots. Elsewhere, Protestants burning Catholics. In the 16th century, fanaticism was ecumenical.

How gloriously out of tune with his times were the words and deeds of Henry. The words : “There must be no more distinction between Catholics and Huguenots. All must be good Frenchmen, and let the Catholics convert the Huguenots by the example of a good life. I am a shepherd king, who will not shed the blood of his sheep, but seek to bring them together by kindness.”

The deeds. When laying siege to Catholic Paris, he had not the heart to maintain too harsh a blockade, lest his capital become a cemetery. He celebrated the taking of Paris with an amnesty, not executions. Rulers not drenched in blood, I find appealing. Henry devoted himself to the beautification of Paris. Among his projects is the Place des Vosges in the Marais district. I come upon children there playing on the grass with joyful abandon, chasing one another and hugging their parents. From the wall of the King’s pavilion, Henry, depicted on a medallion, beams with delight. He enjoyed life and wanted others to do the same. He cared about the welfare of his people, desiring for them “a chicken in every pot.”

During Easter Week in Paris years ago, I came the closest in my life to having a religious experience. Each day that week I attended religious services at Notre-Dame. I loved the magnificence of the Cathedral, the aroma of incense, the processions, the music, the great Western Rose Window. And yes, that the services were conducted in a language I did not understand added appreciably to the awe and majesty of the ceremonies. I visit Notre-Dame on this trip, but do not experience the same emotional and spiritual involvement. For better or worse, I have changed over the years, but in no way do these changes diminish my fond memories of that long ago Easter Week. Walking along the Seine, I come upon chestnuts fallen on the ground with their beautiful mahogany-colored shells. I pick several up and place them in my pocket. They will join the chestnuts I have collected from Central Park on display in my apartment.

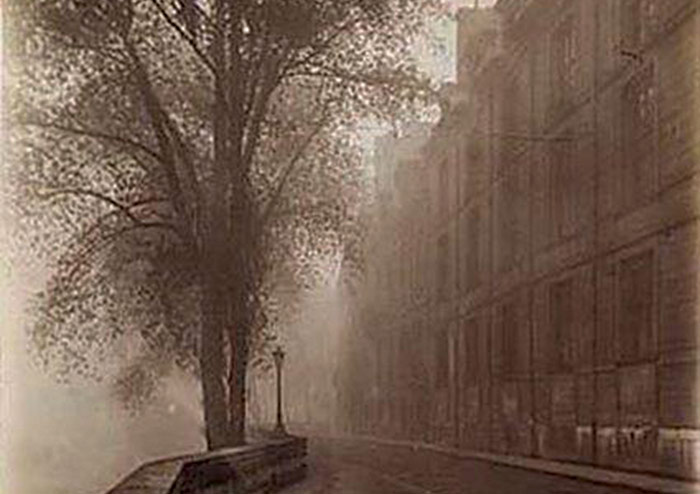

I am drawn to the work of the great French photographer Eugene Atget (1857-1937), for in it

he reveals a heartfelt commitment to his city. His city was Paris, mine is New York. I relate to people devoted to the place where they live. As I learn from the masterly four-volume book series, “The Work of Atget,” by John Szarkowski and Maria Morris Hambourg, Paris for him was both a private passion and a life undertaking. He was very independent and photographed only what he deemed interesting, beautiful or important. He cherished the cobblestone streets and the iron lampposts. One of his early pictures, “Bitumiers,” is an eloquent depiction of workmen laying down a new pavement. On their knees, the workmen, with tools in their hands, tenderly smooth the surface of the freshly poured macadam, as if performing a religious rite.

Atget enjoyed revisiting his favorite parts of the city. Repeatedly he photographed the quais of the Seine and the city’s bridges, especially the Pont Neuf and Pont Marie. He photographed the Luxembourg Gardens regularly for over a quarter-century. On spring mornings he would take pictures of the Ile Saint-Louis, that haven of tranquility and elegance in the Seine, with its views of the splendid flying buttresses of Notre-Dame. Viewing his photographs of wet pavements in fog, I am reminded of my walks along Fifth Avenue in the mist, and these words of Nabokov: “My happiness will remain, in the moist reflection of a streetlamp…. ”