The summer months bring to mind travel thoughts, past and present.

Business being slow, the trattoria owner in Palermo joins me at the table. I show him a chart of Sicilian conquerors. He and I read out aloud the names of the island’s most famous rulers. As the largest island in the Mediterranean, occupying a strategic position between Europe and Africa, and Europe and the Middle East, Sicily has attracted many invaders, among them Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, Swabians, French and Spanish.

Palermo fell to the Arabs in 831. They ruled Sicily for over two hundred years. The first Norman invasion was in 1060-61. These Norman conquerors were “adventurers from northern France earning a profitable living as professional soldiers in southern Italy,” write the authors of “A History of Sicily”, M. I. Finely, Denis Mack Smith and Christopher Duggan. By 1064, the Normans had conquered much of the island.” Experience gained in this operation was to prove valuable two years later in the Norman Conquest of England.”

From my hotel, the Villa Igiea, with its marble terrace, and tropical trees, I look upon the bay of Palermo bordered by mountains and the city. In the gathering dusk, a lone white passenger ship moves across the bay, bound for Naples.

Following the defeat of the Athenian military expedition to Syracuse in 413 B.C., many Athenians avoided capture, and received food and shelter from the local population, by reciting verses from Euripides, the most popular Greek poet among the Sicilians. Eventually finding their way back to Athens, these survivors, in the words of Plutarch, “greeted Euripides with affectionate hearts.” What a tribute to the power of literature! Yet traditional Sicilian hospitality to strangers in distress may also have played a role in the treatment accorded the Athenians. I, too, became the beneficiary of Sicilian hospitality.

I depart from Palermo by car, a stranger to Sicily, not speaking Italian, with the wrong map and struggling with the manual gear-shift of a rented car. On leaving the city, the heavens opened up, unleashing the most violent rainstorm I have ever experienced. I become lost in the countryside. In his novel, “The Leopard,” Giuseppe di Lampedusa wrote, “The term ‘countryside’ implies soil transformed by labor; but the scrub clinging to the slopes was still in the very same state of the scented tangle in which it had been found by Phoenicians, Dorians, and Ionians when they disembarked in Sicily, that America of antiquity.”

I decide to head for Calatafimi, recalling it as the site of a celebrated Garibaldi military victory in 1860 by his red-shirted volunteer soldiers — the March of the Thousand (I Mille) — an important event in the liberation of Sicily from Bourbon rule and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. The sun was already low in the sky. I was not happy with the prospect of driving under these conditions at night. I stop to flag a car down. “Is this the way to Calatafimi?” The driver speaks no English, but gestures to follow him. The only sign of life by the road, a shepherd with his bedraggled flock.

My guide is named Vito. No room being available at the local hotel, he invites me to a family celebration at an uncle’s house and to spend the night with his parents. At the event I am welcomed by family members, among them, Vito’s cousin, a priest.

For dinner, our hostess serves cous-cous with fish sauce in an immense ceramic bowl, sausages, fruit and the sweet pastries so dear to the heart of every Sicilian. The event is joyful. Alas, I am not able to reciprocate, as in classical times, by reciting Euripides in Greek.

Following dinner, I join Vito in a walk along a path taking us by ancient vineyards and olive and fig trees. The night air is fragrant. In the sky of this remote region of Sicily, I see the familiar sight of the Big Dipper. In the morning, Vito maps out for me the route to Segesta, the site of a magnificent Greek temple and theater. We embrace and I depart.

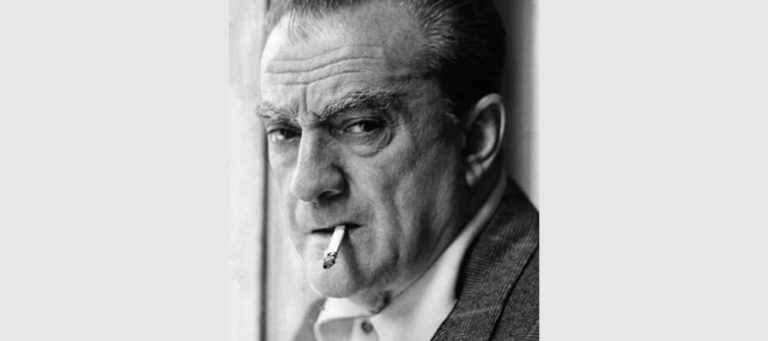

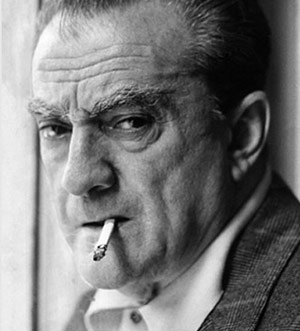

My literary companion in Sicily is Giuseppe di Lampedusa (1896-1957). “The Leopard” is Lampedusa’s only novel. It was published after his death. It is a favorite book of mine, and the film version, directed by Luchino Visconti, a favorite film. Burt Lancaster plays the role of Prince Don Fabrizio, a Sicilian aristocrat. He is brilliant, far removed from his boyhood days in New York’s East Harlem at 106th Street, the son of a mailman, and far removed from his prison film, “The Birdman of Alcatraz.”

At a time of political upheaval in Sicily, the prince, a member of the Bourbon ruling class — “tied to it by chains of decency if not of affection” — finds himself ill at ease with both the old order and the new. The man for the future is Don Calogero, a shrewd peasant who under the new regime is certain to achieve wealth and influence. Lampedusa writes of him:

Many problems that had seemed insoluble to the Prince were resolved in a trice by Don Calogero; free as he was from the shackles imposed on other men by honesty, decency, and plain good manners, he moved through the jungle of life with the confidence of an elephant which advances in a straight line, rooting up trees and trampling down lairs, without even noticing scratches of thorns and moans from the crushed.

Don Calogero looks upon the Sicilian nobility as sheep

to be shorn, but he is fascinated by the prince, a species utterly foreign to him, with his “disposition to seek a shape for life from within himself and not in what he could wrest from others….”

An emissary arrives from Turin to urge the prince to become a member of the Senate and help bring Sicily into the orbit of the newly-found Kingdom of Italy. The prince declines the honor, describing himself as a man of the past. Select Don Calogero, he urges. The emissary understands that this marks a major transformation: A jackal replacing the Leopard. But jackals have their use. This is why the prince fully supports the marriage of his beloved nephew, Tancredi, to Don Calogero’s daughter. (In the film, she is played by the beautiful Claudia Cardinale.) With Don Calogero’s full support, Tancredi will have the wealth and influence to pursue his vast ambitions.

The Piedmontese official, being a northerner, knows nothing about Sicily. The prince feels duty-bound to enlighten this innocent about the dismal record of past conquerors who sought to change Sicilian ways:

Do you really think, Chevalley, that you are the first who has hoped to canalize Sicily into the flow of universal history? I wonder how many Moslem imams, how many of King Roger’s knights, how many Swabian scribes, how many Angevin barons, how many jurists of the most Catholic King have conceived the same fine folly….

Postscript: The latest arrivals to Sicily, and to the nearby island of Lampedeusa, come from Africa, the Middle East and Asia, not as conquerors, but as refugees traveling in fragile crafts upon a hostile sea. Above them, “the stars were glittering away, producing thousands of degrees of heat which were not enough to warm one poor old man.” (Lampedusa)