In his marvelous book, “Flaubert’s Parrot,” JulianBarnes writes: “It’s easy…not to be awriter. Many people aren’t writers and very little harm comesto them.” Those who do become writers don’t get off so easily. Here is Flaubert on the frustration writers encounter: “Language is like a cracked kettle on which we beat out tunes for bears to dance to, while all the time we long to move the stars to pity.” (“Madam Bovary”) Flaubert must have worked long and hard to create this marvelous sentence. His credo: “May I die like a dog rather than hurry by a single sentence that isn’t ripe!

The finest writers experience difficulties when at work. In his 1855 journal, Thoreau evaluates his literary efforts: “Playing with words, – getting the laugh, – not always simple, strong and broad.” This is Whitman’s advice to himself as he prepares the second edition of “Leaves of Grass”: Do “Only that which / is simply earnest / meant…unadorned / unvarnished….”

Samuel Johnson said that a writer can write anywhere or anytime “if he will set himself doggedly to it.” Doggedness was essential to the completion of his “Dictionary.” Plunge ahead, urges Joyce, for “In the writing the good things will come.”

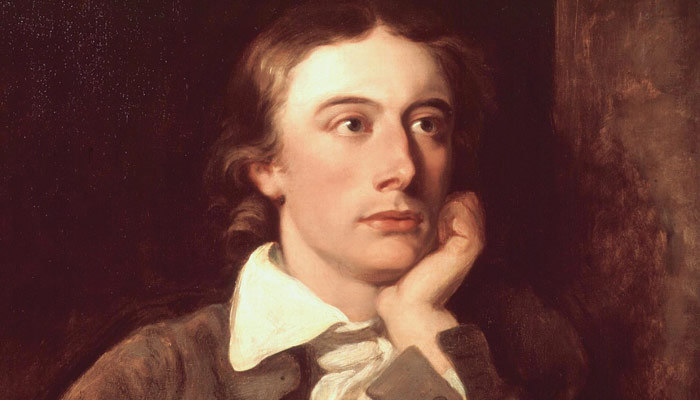

At Yalta,Chekhov liked to have prints of favorite writers on his desk: Pushkin, Tolstoy, Turgenev. Isolated thereby illness, he found companionship in their presence. Keats, when he had gone to the Isle of Wight to work on “Endymion,” came upon a print of Shakespeare in the passage way of his rooming house. As Walter Jackson Bate relates in his eloquent biography of Keats, the landlady allowed him to move the print into his room where, after taking down a print of a French ambassador, he hung the Shakespeare above his books.Though he stayed at the rooming house only a week, the landlady insisted that he take the print with him. Wherever Keats wrote, he always kept it by him. God bless Mrs. Cook, the landlady. By her generous act, she served literature in a way few have done.

Writing is a solitary activity. To make it less so, I enjoy writing in public spaces, like on a park bench in Central Park. Or, on a New York City subway. Here I find no shortage of company, though rush hour trains are not desireable. It is not easy to write standing up with a neighbor’s elbow in your face. By mid-morning, things calm-down. Like Thoreau, I carry paper and pencil. (The family pencil business supplied Thoreau with plenty of pencils.) I set to work on the train. The interiors of subway cars are surprisingly quiet and the movement of the train is smooth as it speeds underground along silver steel rails. Subways, however, are not without problems, like conductors who disturb the quiet by unnecessarily imparting too much information, having fallen in love with the sound of their own voice. Or defective train announcement systems that produce ear-splitting, unintelligible noise. The sounds of words are important tome. I like to read them aloud. Mumblers instill disquiet among fellow passengers. Not infrequently, the person sitting next to me moves to another part of the car. This leaves more space for me.

Upon completion, I send the piece to a publication. Then the waiting period begins. It can be lengthy. “The postman becomes a source of hope at a distance,” writes R.K. Narayan in “My Days,” and if the manuscript has been rejected, “of despair when he arrived.” In his short story, “My Jubilee,” Chekhov portrays a character who whimsically offers to celebrate the termination of his writing career on having just received his second thousandth rejection. And in another Chekhov story, a writer is advised to save on postage by not submitting further drivel. On the return of an article, my policy is not to despair, but to send the rejected piece to another publication that very day.

Chekhov had his own share of turndowns. They came, not by mail, but in the “Letter Box,” the magazine section where editors commented on submissions. Ernest J. Simmons, in “Chekhov, a Biography,” writes how “With cold, trembling fingers he turned the pages to the fine print of their ‘Letter Box’ sections and ran his eye expectantly over comments to would-beauthors.” Some of the comments directed to Chekhov were not encouraging. “A few witty comments cannot obliterate such woefully insipid verbiage.” Or, “You have ceased to flower; you are withering. A pity….”

These lacerating comments make the editors I deal with seem saintly by comparison. Harrison Salisbury, the founding editor of the Op-Ed page at “The NewYork Times,” sent charming rejection notes. In his response to a labored piece of mine on Hans Sachs, hero of Wagner’s opera, “Die Meistersinger,” Salisbury wrote, “Sorry — it’s no sale on Sachs!” After accepting my first submission, he turned down the next two. “Well, gosh — I guess the old average takes a beating — down to .333. But keep on trying.”

Other rejection notes stung, though with the passage of time they now seem mildly amusing. “Really, there’s no over-arching theme. What did you have in mind?” I especially dislike the cold, printed, unsigned insertions, “A self-addressed, stamped envelope should accompany all submissions.”

Chekhov did not become one of the greatest writers by only receiving rejection notes. While a medical student, he received this communication from the St. Petersburg humor weekly, Dragonfly : “Not at all bad. Will print what was sent. Our blessings on your further efforts.” Tears come to my eyes when I read the concluding line. It must have meant so much to the impoverished young medical student.

For most writers, fiscal realities are frightening. Early on, mother suggested I attend law school. I did so, avoiding a life of penury. “My first year’s income from writing,” R.K.Narayan wrote, “was …about nine rupees and twelve annas.” He “unexpectedly” had a piece accepted by “Punch.” “This was my first prestige publication (the editor rejected everything I sent him subsequently ) and it gave me a talking point with my future father-in-law.” (Not much of a confidence builder for the prospective in-law.) Of his play, “Krapp’s Last Tape,” Samuel Beckettwrote : “Seventeen copies sold, of which eleven at trade prices in free circulating libraries beyond the seas. Getting known.”

Writing has roller coaster moments. Jason Epstein, Vice President at Random House, based on an outline I prepared with an architect friend, accepted our proposed book on the subject of freeing city streets from the tyranny of the automobile. My spirits soared. Minutes later, as I sat in his office, he summoned a senior editor to work with us on the book. She told us she had no interest whatever and left the room. My spirits sank. Undeterred, Jason summoned his secretary who was typing just outside his door. “Susan, you’ve wanted to have a book. This is it.” Susan was thrilled. My spirits soared. Months later, however, Jason told me that because of difficult financial times, he was dropping the hardcover edition. My heart sank, because that meant no reviews and no library sales. But then the “Times” changed its policy on original paperbacks and Susan persuaded an editor to have the book reviewed. It turned out to be a full page laudatory review in the “Times” Sunday book section. My spirits once again soared. This whole experience gave me a confidence about writing I never had had before. (Susan Bolotin has gone on to become Publisher and Editorial Director of Workman Publishing. )

And there can be wonderful surprises. Two years ago, Krishna Kumar Mishra, editor and publisher of this magazine, read a book collection of my essays, “My New York, A Life in the City.” He liked them. Out of the blue, from far away Mumbai, I received an invitation to write a monthly column, “Letter from New York,” for his new magazine. This is my 28th column.

Writing has taught me perseverance, a valuable lesson in life. And it has given me immense pleasure and expanded my world. “Through good report and through ill report…, through sunshine and through moonshine,” in the words of Edgar Allan Poe, “we [writers] continue to toil. Nothing hurts our curiosity or our hope.”