In my professional career I was fortunate to have met some of the ‘really courageous’ Supreme Court judges like Justice V R Krishna Iyer. I strongly feel there is nothing to be proud of our judicial system. My generation can’t forget that there was a dark period during the Emergency (1975-77) when the Supreme Court bowed down to the diktats of the Indira Gandhi government and robbed the citizens of the country of their final hope of grievance redressal.

So when as Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra’s 13-month tenure came to an end, and in his last public address he said, “It cannot tilt to either side owning to anyone’s aggressive views. The lady of justice is blindfolded to signify neutrality, since each case whether involving a greater or smaller ramification is the same for us,” I was not convinced. Sadly that’s not the truth we come across. We’ll be doing a blunder if we ignore the fact that the commitment of the judges and lawyers towards the judiciary has not stood the test of time in India. In the eyes of Indian judiciary the tears of a poor man is not equal to tears of a rich man.

We are often told that Indian judiciary is one of the most robust institutions in the world. Justice Misra very proudly announced that, “Our judges are far ahead from their counterparts in other countries, shining with the abilities to resolve mindboggling number of cases.” Again an unbelievable statement.

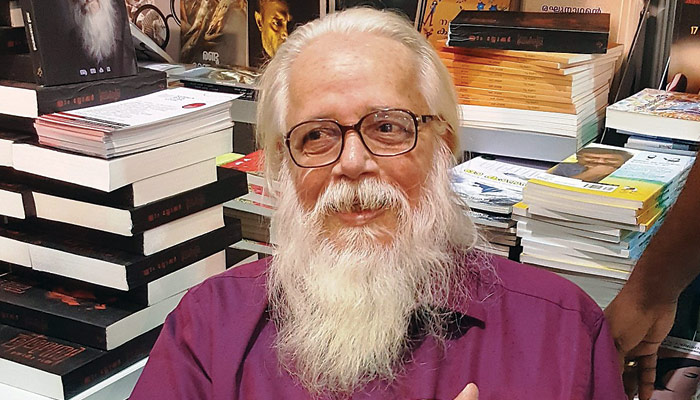

I would like to mention, in the light of the above statements, the ISRO scandal. The prime accused in the supposed Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) spy scandal Nambi Narayanan, the scientist, was first arrested in 1994. Later he was honourably acquitted. Now the gracious Supreme Court has awarded Rs 50 lakh as ‘compensation for the damage to his reputation.’ The Court has also ordered an enquiry into the circumstances in which ‘this absurd case’ was fabricated. The Court said that ‘the entire prosecution had been borne out of fancy and had been malicious.’ But those who were instrumental in filing the false case and who in fact ruined Narayanan’s life have not been punished. Surprisingly, the scientist was acquitted by courts just two years after the scandal broke but the case trudged on for decades. Again judiciary will proudly say that justice is done. Really?

I’m unable to understand how the Court has decided the quantum of compensation. What goes into the calculation? And why the nameless undertrials, who languish in the custody of the state for years, and are then released for want of evidence, should be deprived of this magnanimity? But how to calculate how much are they worth after they have spent years in custody, not tried, let alone convicted, but merely awaiting the attention of a callous state?

An engineer by training Narayanan, now 77, joined India’s then nascent space industry in 1966. He was one of the chief architects of the ‘Vikas’ engine that made missions like Chandrayaan and Mangalyaan possible. Until the time of his arrest, Narayanan had had a distinguished scientific career. He was India’s leading specialist in liquid propulsion engines – a fact the government of India had recognized. In fact, he was the first one to advocate liquid propulsion technology for India’s rockets. At that time, India could only handle solid fuels for its experiments, and investing in a futuristic idea of liquid propulsion was considered too ambitious. Liquid fuels generate more energy and burn slower than solid fuels which, however, are easier to handle and provide greater initial thrust to the rocket. Narayanan’s boss at ISRO Vikram Sarabhai was so impressed that he ensured that Narayanan went to Princeton University for higher studies on rocket propulsion. After his return from Princeton, Narayanan was able to clinch a profitable deal with French company SEP that allowed several ISRO scientists to work on the development of the French Viking engine that had liquid propulsion. The ISRO scientists, led by Narayanan, spent five years in France mastering the know-how of liquid technology that was used to develop ‘Vikas’.

When the scandal broke out Narayanan was heading the cryogenics project. Cryogenics is the technology of low temperatures. For carrying heavier payloads and going much deeper into space, GSLV needs greater amount of energy. India had been using Russian-made cryogenic engines to power its earlier GSLVs. Due to the scandal it was only after two decades that it has been able to master the technology and started using indigenous cryogenic engines in its rockets.

Let us have a look at the case in a chronological order: On October 20, 1994, the Kerala police arrested Maldivian native, Mariam Rasheeda, for allegedly overstaying her visa who was in Kerala to get her co-national Fauzia Hassan’s child admitted into a higher education course in the state. The police are said to have found in Rasheeda’s phone records calls to Narayanan’s junior colleague D Sasikumar who was arrested shortly after, and so was Hassan. This was followed by the arrest of a businessman, K Chandrashekhar from Bangalore, who was a representative of the Russian space agency Glavkosmos. Narayanan and his colleagues were accused of passing on top secret information on the Indian space programme to Pakistan through the Maldivian women. On November 30, 1994 Intelligence Bureau searched Narayanan’s house and found 75 kilograms of classified ISRO documents, which he was supposedly selling and he was arrested.

Narayanan was branded a traitor and his family was subjected to harassment. He confessed that he was tortured during the 50 days he spent in police custody. He was beaten and slapped as his interrogators pressed him to just cough up any Muslim name. Mariam Rasheeda had said that one of the investigating officers in the case had sought sexual favours from her, and decided to frame her for espionage when she refused his advances. Rasheeda and Hassan were in the custody of the police for nearly two to three years.

The case was transferred to the CBI, in December 1994. In May 1996, the CBI submitted its report to a Kerala court, dismissing the charges against the accused as baseless. The CBI accused the Kerala police’s special investigation team of being unprofessional in its investigation and recommended disciplinary action against the probe officials. ISRO also clarified that it did not classify any of its documents and it was usual for scientists to take the documents/drawings required for any meetings/discussions to their houses for study purposes. A Kerala court accepted the CBI’s report absolving the accused and recommended action against investigating officers but Kerala government was not satisfied and took the case back from the CBI and reopened the investigation.

Giving a twist, hold your breath, Kerala high court also upheld the state government’s decision to reopen the investigation. However, after two years, in April 1998, the Supreme Court quashed the state government’s decision to reopen the investigation and ordered the state government to pay Narayanan Rs1 lakh as compensation. In March 2001, National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) ordered the state government to pay Narayanan Rs10 lakh as compensation. In June 2011, Kerala government decided not to pursue disciplinary action against the investigating officers.

In September 2012, the high court ordered the state government to pay the compensation of Rs10 lakh which had been pending. In October 2014, high court directed the state government to reconsider disciplinary action against the investigating officers, but in a dramatic twist in March 2015, the high court approved of the state government’s decision to not pursue disciplinary action against the investigating officers. In September 2018, the Supreme Court ordered the state government to pay Narayanan Rs50 lakh as compensation. It has set up a committee to decide disciplinary action against the investigating officers.

All those accused in the spy case suffered. K Chandrashekhar died a pauper. He was in the hospital in his last days since he could not settle his bills. His last days were lived in misery. Another accused in the case, S K Sharma, is terminally ill right now in Bangalore. It is not just a few individuals who have suffered. The country also suffered as the Indian space programme got delayed by so many years. After this scandal Russians became hostile towards India as the case caused humiliation not just to Indian scientists but to their counterparts in Russia. India could have got from Russia equipment and technology but suddenly all those sources were cut off.

There are not many faces in the history of Indian judiciary whom we can salute. People of my generation remember Justice HR Khanna and his role during the gloomy days of the Emergency. Even New York Times was compelled to publish an editorial, and I quote here which sums up the functioning of the highest court during the darkest hour in India’s history:

“If India ever finds its way back to the freedom and democracy that were proud hallmarks of its first eighteen years as an independent nation, someone will surely erect a monument to Justice H.R. Khanna of the Supreme Court. It was Justice Khanna who spoke out fearlessly and eloquently for freedom this week in dissenting from the Court’s decision upholding the right of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Government to imprison political opponents at will and without court hearings… The submission of an independent judiciary to absolutist government is virtually the last step in the destruction of a democratic society, and the Indian Supreme Court’s decision appears close to utter surrender.”