Growing up in New York City introduced me to immigrant communities. We lived at 70 East 96th Street, between Madison and Park Avenue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. A few blocks away was an Irish community. A large number of the Irish came to New York City as the result of an immense tragedy, the Irish Potato Famine (1845-1849) where one million Irish died and one million had to leave the country, there being no future for them in their own land. Years later, I came to learn as I hiked along the Sky Road in Connemara, visiting the remains of villages abandoned during the Great Famine, that the Irish have endured great suffering as a people. Many came to the United States. By 1850, the Irish made up a quarter of the city’s total population of 590,000. Later, Irish labor helped build Central Park and the subway system. They became bus drivers and police officers, but a sizeable number, being poor and lawless, landed in prison.

I was born in 1937. In the 1940s, the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, celebrating the patron saint of Ireland, ended at 96th Street near the apartment house where we lived. This was the city’s largest and longest parade, starting up Fifth Avenue at mid-day and ending about 9pm at 96th Street. Every March 17th, the Irish took over the city. A festive and raucous day.

To flaunt any English association on that day was not wise, so I had to be careful, because I attended St. Bernard’s School two blocks away. My school was founded in 1903 by two Englishmen. At lunch we ate shepherd’s pie with Worstershire sauce, a quintessential English dish; performed Shakespeare plays and were almost the only boys’ school in the city where soccer was played. Our teachers were called masters and we sang with gusto songs concluding with lines like these:

Now the Saxon flees before us;

Victory’s banner floateth o’er us!

Raise the loud exulting chorus,

‘Britain wins the field.’

The aroma on 96th Street at the conclusion of the parade was a mix of brewery and hospital emergency room. The Department of Sanitation had an immense job collecting beer bottles along the parade route. On this day, my friends and I thought it wise to suspend an exciting activity of ours – tossing water bombs out of the 16th floor living room window, since this might incite a storming of the building by hotheaded Irish revelers on the street below. (Growing up, I was far from being a model of good behavior.)

The most dramatic encounter I experienced with my Irish neighbors occurred in a one block park in the center of Park Avenue between 96th and 97th Streets. I love trains! I would go there to look down from 97th Street on the railroad tracks below, watching departing trains as they emerged from the tunnel under Park Avenue, heading for the suburbs and Boston, and incoming trains heading for Grand Central Terminal. My favorite train scene in a movie occurs in “Pather Panchali,” the masterpiece of Satyajit Ray, where Apu and his sister, Durga, standing in a field in Bengal, watch with wonderment the passage of a train in the distance, black smoke trailing from its locomotive.

I also enjoyed reading books on a bench in the park. At age 12 – my age at the time – mother was reading Russian, French and English classics. My selection was not as lofty, being the Hardy Boys series where the reader follows with breathless anticipation the adventures of Frank and Joe Hardy, teenage sleuths, solvers of mysteries, my favorite in the series being, “The Sign of the Sinister Signpost,” more, perhaps, for the alliteration in the title than the story, since I remember nothing of the story today.

So here I was, reading, doing harm to no one, when I became aware of five boys encircling the bench where I sat. I sensed that no good would come to me from this encounter. Their eyes alighted upon my beloved baseball glove beside me. I spent hours each day rubbing the glove with neat’s-foot oil to preserve the quality of the leather. I believe I enjoyed caring for my glove more than playing the game, since I was never any good at it.

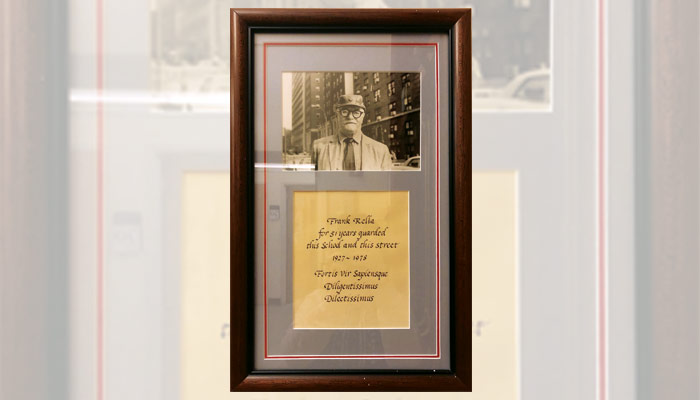

I leapt up from the bench and pushed my way out of the circle, running as fast as I could along Park Avenue. I was not going to let anyone steal the glove, but my tormentors, in full pursuit, were gaining on me. And then, on the street, I had the enormous good fortune to encounter Mr. Frank Rella, the school custodian. He was both a gentle man, making sure that the younger boys at school were crossing heavily – trafficked Madison Avenue in safety, and positioning himself by the school front door to straighten the ties of disheveled students. On frigid early winter mornings, he flooded the yard so we could ice skate.

But there was another side to Mr. Rella. He was known as the school’s “resident strong man,” being built like a football player, with a powerful chest and huge arm muscles acquired from years of working at his other job as the neighborhood ice man. He carried blocks of ice on his shoulder for tenement dwellers who could not afford refrigeration, instead, storing milk and other food items in their ice box. Also, he had fought in the Italian army in Ethiopia. Any one messing with him did so at their peril.

Mr. Rella had sized up the situation in an instant. One of his flock, namely, me – a St. Bernard’s boy – was in need of protection. He was the shepherd coming to the rescue. (Pope Francis has called upon his priests “to be shepherds with the smell of sheep.”) Being Italian, Mr. Rella had a sense of drama. He walked over to a garbage can and removed an empty whiskey bottle, smashing the bottle against the brick wall of an apartment building. With this weapon in his right hand, he lunged at my tormentors. They saw coming at them a muscled, mustached, mountain of a man menacing them with jagged glass, the remains of the bottle. Turning on their heels, they fled the scene, not to be seen again.

From this experience, Mr. Rella and I formed a bond that lasted through my remaining time at the school and into the future when I would see him in the neighborhood with his ice cart. He served the boys of the school for 51 years, from 1927 – 1978. A plaque honors him in the school lobby. It bears a Latin inscription concluding with the word, “Dilectissimus” meaning, “most beloved.”

Two Irish poets:

I never saw sad men who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

We prisoners called the sky,

And at every careless cloud that passed

In happy freedom by.

“The Ballad of Reading Gaol” by C.3.3., Oscar Wilde’s cell number at Reading Gaol.

History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave,

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

“The Cure at Troy” by Seamus Heaney