New York City. June 15, 1904, began as a beautiful spring day. Sunshine, cloudless skies. On such a day, nothing possibly could go wrong, but the day was to end in disaster, as did September 11, 2001. The two deadliest days in the city’s history, with each exceeding a thousand deaths.

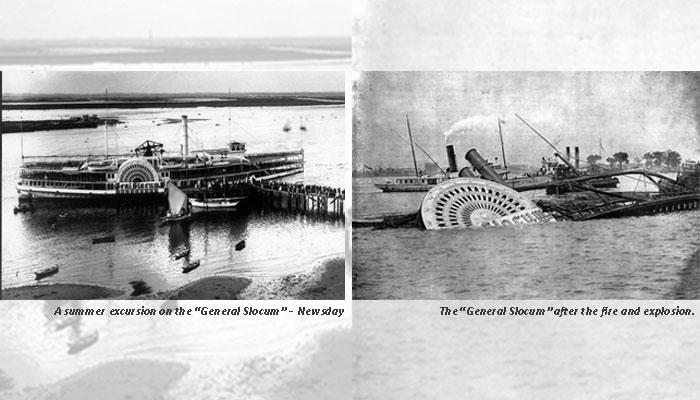

Day One: The burning and explosion of the Steamboat “General Slocum” following its brief journey up the East River and then through the Hell Gate. A description of the event, written years later from afar by James Joyce, in “Ulysses”: “Yes, Sir. Terrible affair that ‘General Slocum’ explosion. Terrible, terrible! A thousand casualties. And heart rending scenes….Most brutal thing….Not a single lifeboat would float and the fire hose all burst.” (Joyce sets “Ulysses” on a single day, June 16, 1904, the day following the “Slocum” disaster.)

Day Two: The destruction of the World Trade Center, replacing the “General Slocum “ as the city’s worst disaster. The details of the World Trade Center are known to almost every New Yorker, those of the “Slocum,” to only very few. I was not among them. To remedy my ignorance, I have been reading two excellent books: “The Burning of the General Slocum” (1981)) by Claude Rust, dedicated to his “Grandmother, Charlotte May, and all the others who died on the General Slocum that day,” and “Ship Ablaze, The Tragedy of the Steamboat General Slocum” (2003) by Edward T. O’Donnell, dedicated “to the innocents in the catastrophes of 6/15/04 and 9/11/01… and the bereaved left behind….” Both books are the result of extensive research by the authors. Both are written from the heart.

The “General Slocum” was a triple decker excursion boat, with wooden paddles, built in 1891, and named after a Civil War hero. She was chartered for $350 for a one day picnic excursion by St.Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Manhattan on East 6th Street, a neighborhood with a large German immigrant population referred to as “Little Germany.” The event: to celebrate the completion of the church’s Sunday school year.

The Reverend George Haas, pastor of St.Mark’s, took his place by the crowded gangplank on the 3rd Street pier to welcome members of the congregation, decked out in their finest clothing. They were largely mothers and children, the event being on a weekday when many of the fathers were at their jobs. The crowd cheered the arrival of the band. The pastor confided to his wife that he had worked hard to make this year’s excursion better than any before. He greeted members of his flock in German and English. For an hour, a steady stream of passengers boarded the vessel. They numbered about 1,300.

Claude Rust writes: “Finally, at 9:40, the lines were cast off, the pilothouse rang for slow ahead, a tremor, a struggle for movement ran through the vessel, water boiled beneath the giant paddle wheels, children thrilled as the deck’s vibration tickled their feet. Then they were off. The band struck up a favorite German hymn, and the people one by one took it up until all were singing what was to be their own requiem: ‘A mighty fortress is our God, our helper. He amid the Flood.’”

The vessel proceeded north, passing Bellevue Hospital on the East bank at 26th Street and Blackwell’s Island in the middle of the river – later to be renamed Welfare Island, and today called Roosevelt Island. “Blackwell’s was the city’s back closet, where it hid away hospitals, insane asylums, penal institutions. In these tombs for the living, patients and inmates listened to the tinkle of laughter and music drifting across the water from another world.” (Rust)

The “Slocum” approached the treacherous waters of Hell Gate where the waters of New York City Harbor and the East River met those of Long Island Sound. As the vessel eased her way carefully through the narrows of Hell Gate, onlookers on Wards Island “saw smoke coming from two forward portholes under the main deck,” but the officers “in the pilothouse were staring intently toward the exit from Hell Gate dead ahead, apparently unaware. Many of the Wards Island people ran to the shore waving wildly and pointing to the danger below. The excursionists waved back good-naturedly, wondering at the curious behavior of the people on shore.” (Rust)

Comments of two crew members on an approaching vessel: “That smoke’s getting thicker every minute.” “She’s afire!”

The burning boat continued on past a dredge. The operator “saw a burst of flame forward. He blew four blasts on the dredge whistle to alert the pilots, but the ‘Slocum’ kept going….Suddenly, in the middle of a popular tune, the band stopped playing. The boat exploded into flame.” (Rust)

Pandemonium ensued on board. “The flames were on their way now, racing through the boat without a metal door or bulkhead to stay them. Upward and aft a strong vengeful wind carried the hot fumes and fire through the once cool promenades and cabins, turning the carefree crowd of a few minutes before into a pack of maddened creatures scrambling for safety….Screaming women and children were running blindly about, seeking safety anywhere…..Wails of dismay….The [life] preservers, which had rotted in the racks for thirteen years, fell on the passengers’ heads and burst in a shower of powdered cork….The confused captain was giving conflicted orders to the engine room: “Full speed! Stop! Go ahead! Slow! Full speed! Ed, it’s all over with her, we can’t save her….Beach her on North Brother Island.” Women threw their children overboard and followed them….Pastor Haas: “One by one I saw them sink around me, but I was powerless to do anything. I cannot swim. I went down once, and when I came up, I clutched at the blade of the paddle wheel.” (Rust)

Badly burned, he was saved by a tug. Never again did he see his wife.

Doctors and nurses rushed to North Brother Island to tend to the injured – some half crazed by fright – as police officers and volunteers were laying out on the shore the bodies of many dead pulled out from the waters. Piers became temporary morgues where the dead lay in coffins packed with ice.

Edward O’Donnell writes: The task before Pastor Haas was enormous. “The fire not only swept away half of St.Mark’s membership, but also compelled scores of families to move away from a neighborhood so intimately linked with the death of their loved ones…. Nearly one year after the fire, a survey… reported that 170 (28 percent) of the 622 families known to have been on the ‘Slocum’ had moved out of Little Germany….By 1910 only a handful remained and Little Germany was practically gone…..[Pastor Haas ] stayed on for seventeen years after the fire and ministered to an ever-shrinking congregation.”

On a recent Sunday afternoon, I visit Tompkins Square Park, a few blocks from St.Mark’s Church in the former “Little Germany,” where a modest – sized stone of Tennessee marble, the Slocum Memorial Fountain, serves as a reminder of those who died. Two young children, a boy and girl, are depicted on the face of the stone, along with these words: “They were earth’s purest children, young and fair.” The memorial was donated by the Sympathy Society of German Ladies, many of whom lost their children in the calamity. It is drenched in parental tears.