For those who fear that resort to referendums might erode parliamentary democracy, the recent past provides unhappy confirmation. The hysterical cry of the enemy of the people against the London High Court’s decision that only parliament is entitled to make and repeal laws, demonstrates that some Brexiters do not care about parliamentary sovereignty. Their cause is rather dictatorship of the majority.

The phrase “enemy of the people” — used to turn opponents into outlaws — has an ignominious pedigree. During the French Revolution, Robespierre threatened “les ennemis du peuple” with death. The Soviet Communists labelled opponents “vrag naroda”. The Nazis labelled them “Volksverräter”. The aim was always the same: to establish a dictatorship in the name of the people, thereby entitling the rulers to deprive opponents of freedom, even their lives, as the people’s condemned enemies.

In practice, only a government can implement the will of such a majority. As constraints upon the government are discarded, in the name of the majority, the government may become a dictatorship that rules in the people’s name. Its popularity is often used to justify the elimination of restraints and even the suppression of opponents. An assault on judicial independence is often a part of such a story.

The resort to referendums as a way of deciding constitutional questions undermines parliamentary democracy.

The consequences for Europe of Italy’s referendum result are not as obviously dramatic as those of Britain’s referendum in June. The British voted to leave the EU. The Italians have simply rejected some complex constitutional changes, which many experts regarded as ill conceived in the first place. And yet Brexit and the Renzi resignation do form part of the same story. The European project is under unprecedented strain. Britain’s decision to leave is the most striking evidence of this. But, in the long run, the unfolding crisis in Italy could pose a more severe threat to the survival of the EU. The reasons for this are political, economic and even geographic.

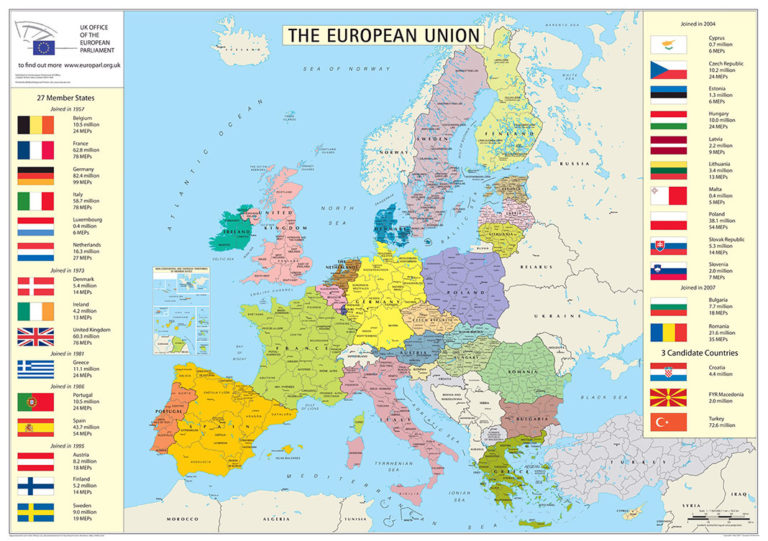

Italy, unlike Britain, is one of the six founding members of the EU. The original European Economic Community was founded through the Treaty of Rome, signed in 1957. While the British were always the most Eurosceptic of the big EU nations, the Italians were traditionally the most enthusiastic unifiers.

But attitudes to the EU in Italy have changed profoundly — in response to the country’s long economic stagnation, the euro crisis and fears over illegal migration. It is hardly surprising that Italian voters are disillusioned with the status quo. Italy has lost at least 25 per cent of its Industrial production since the financial crisis of 2008. Youth unemployment stands at almost 40 per cent. Unsurprisingly, many Italians associate the advent of the euro with a near-depression. And indeed some economists believe the euro has been disastrous for Italy’s competitiveness, taking away the tools of currency devaluation and creating a deflationary environment that increases the debt burden.

Mr Renzi’s departure may not prove a decisive event. But, so long as the Eurozone fails to deliver widely shared prosperity, it will be vulnerable to political and economic shocks. Complacency is a grave error.

A severe challenge is the divergence in economic performance among the members of the single currency, with deep recessions in a number of member countries (notably Italy) and stagnation in others (notably France). According to the Conference Board , a research group, between 2007 and 2016 real GDP per head at purchasing power parity rose 11 per cent in Germany, barely changed in France, and fell 8 per cent in Spain and 11 per cent in Italy. It will probably take until the end of the decade before Spanish real incomes per head return to their pre-crisis levels. In Italy, this seems unlikely to happen before the mid-2020s. The painful truth is that the Eurozone has not only suffered poor overall performance, but has also proved to be a machine for generating economic divergence among members rather than convergence.

The combination of weak aggregate demand with huge post-crisis divergences in economic performance has turned the Eurozone into an accident waiting to happen. True, it is quite possible that the situation will stabilise. But the interactions between economic and financial events and political stresses are unpredictable and dangerous.

What the Eurozone needs most is a shift away from the politics of austerity. In its most recent Economic Outlook the OECD, a club of mostly rich nations, makes a cogent, albeit belated, plea for a combination of growth-supporting fiscal expansion with relevant structural reforms. This is most relevant to the Eurozone because that is where demand has been weakest and the fetish over fiscal deficits most exaggerated. In the big Eurozone economies, net public investment is near zero.

Those who matter — the German government, above all — view public borrowing as a sin, regardless of its cost. The political and economic impact of breaking up the Eurozone is so great that the single currency may well soldier on forever. But it has by now become identified with prolonged stagnation. Those member countries with the power to change this approach should ask themselves whether it really makes sense. It is time for the Eurozone to stop living dangerously and start living sensibly, instead.