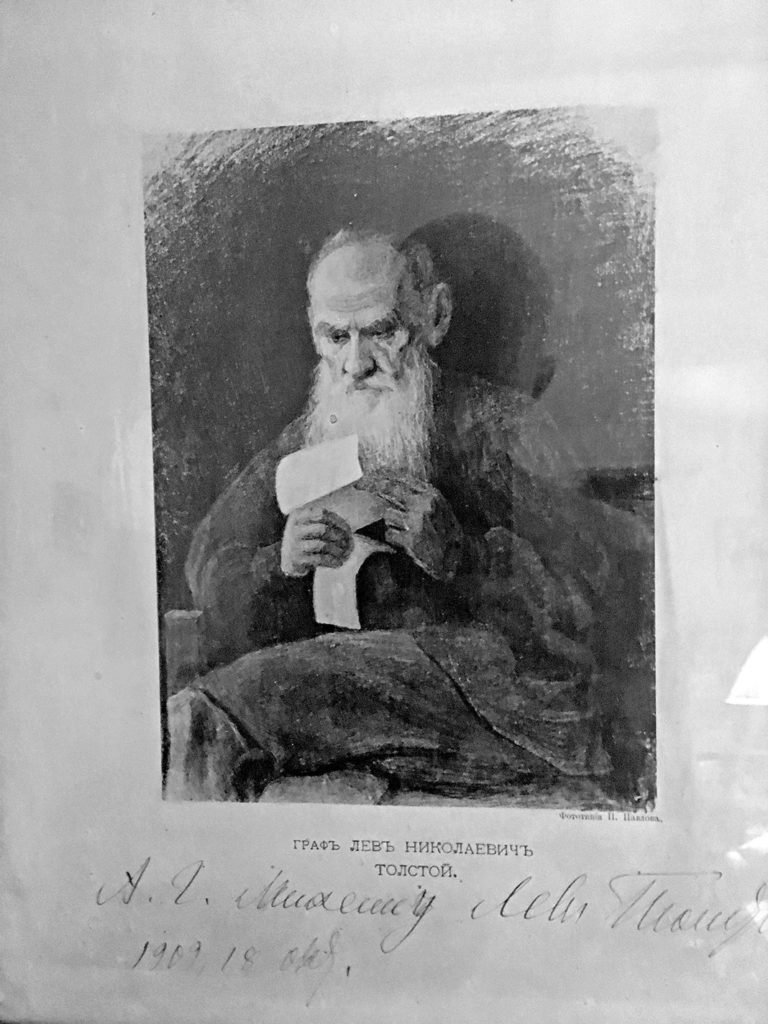

On my mantel, the place of honor is accorded to this drawing of Tolstoy, inscribed by him to my grandfather who spent three days in 1909 at his country estate, Yasnaya Polyana, recording Tolstoy’s voice for a charitable project. They conversed in Russian, French and English. Tolstoy read the thoughts of leading world thinkers he had compiled. This is my proudest possession.

How small to others, but how great to me! (Ovid) I have lived in the same 3 1/2 room, sixth floor apartment, at 155 East 73rd Street, since 1964. When I began apartment – hunting, two years after finishing law school, this was the first apartment I looked at, being located on a lovely street of carriage houses between Lexington and Third Avenues, in a ten story building built in 1929, with an attractive lobby and views of brownstone gardens and the dome of Saint Jean Baptiste, my favorite church in the city. And with a perfect location: three blocks from Central Park.

I immediately fell in love with apartment 6D. Other apartment searchers thronged the rooms. I caught fragments of their conversation.”Too small.” “Our furniture will never fit.” Here I was at a distinct advantage, owning only one chair at the time. For me, small was good. (Thoreau: “I had three chairs in my house [on Walden Pond]: one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”) I turned to the building superintendent and said, “Yes!” For a newly minted lawyer earning $6000 a year, to live on the fashionable Upper East Side without paying an exorbitant rent, in the wealthiest postal zone in the nation, was the closest to heaven I was likely ever to achieve.

Fifty-three years later, I occupy the same premises. I am like a barnacle attached to a ship’s hull. A few years ago, when the apartment was about to be painted – the walls were screaming, “paint us!” – the idea came to me to vacate the premises and stay at the Hotel Wales at 93rd Street and Madison Avenue. On arriving at the hotel, I became ill. Twenty blocks travel were too much for my nervous system to absorb. I was home sick for the pavement and carriage houses on my block. A speedy recovery ensued two days later upon my return to 73rd Street.

I grew up at 70 East 96th Street, inheriting my strong attachment to real estate from mother who lived in her 16th floor apartment for decades. Joseph Brodsky, the Russian-born essayist and poet, writes of Russians – mother being one, and through her, me being half-Russian: “I am prepared to believe that it is more difficult for Russians to accept the severance of ties than for anyone else…. For us, an apartment is for life, the town is for life, the country is for life. The notions of permanence are therefore stronger; the sense of loss as well.”

Years later, long since ensconced in my apartment, I return home one night and am shocked to find books scattered on the living room floor. Has the apartment been burglarized? Nothing so dramatic. A pile of books has toppled over from its own weight.

My apartment is awash with books, a testament to a penchant for both literature and clutter. With no cellar or attic – those safety nets for ownership excess – books continue to pile up. My books are in disarray, with no alphabetical or subject-matter coherence. Rather than spend time searching for a favorite book, I go out and buy another copy. I now own several copies of “David Copperfield” and “The Plague” by Camus.

My apartment contains an unusual mix of things. By the fireplace is a wooden lobster buoy I found on the Maine coast and a copper pitcher from India. In front of the fireplace is my bicycle. I consider a bicycle a work of art to be seen, not consigned to a dark basement room. On the mantel above the fireplace will be found a home run baseball from a Yankee game; a boomerang, as yet, unused; a bottle containing sand from the Syrian desert; a bust of Richard Wagner; a cloth camel from Egypt; a pair of pewter candlesticks; a framed 19th century map of the subcontinent; a photograph of Pushkin I took, his statue adorned with fresh flowers placed by devoted admirers at his feet, on his shoulders, every where a flower could be placed; a crayon-drawn American flag from Public School 112 in Brooklyn where I served as school principal for a day; my god son’s creation, a clay gargoyle given to me decades ago, and the facsimile of a gold key made in 1812 for the front door of New York’s newly built City Hall.

Elevators play an important role in the lives of New Yorkers. I grew up living on the 16th floor of an apartment house. On occasion, the elevator men would go on strike. This was hard on mother and other older people in the building, but the superintendent, being a kind man, would sneak mother up on the back elevator. Meanwhile, my dog and I walked down and up 16 flights of stairs several times a day. We found the experience a hoot. For Penny, each floor was an enchanting place of new-found aromas.

Early on, I learned not to discuss sensitive matters – business or personal – while riding in an elevator. Everyone listens, while pretending not to. Once I was in an elevator in TriBeCa that got stuck in the shaft. To pass the time, I read aloud to my fellow passengers the Department of Buildings Passenger Elevator Certificate posted in the elevator: “13 maximum no. of persons. 2000 maximum no. of pounds.” We numbered less than 13. That was easy to determine, but what about our collective poundage? I took out the pencil and notebook I always carry and questioned each passenger as to their weight. Some were amused, others not. But it did help time pass until our rescue.

In my apartment house elevator on East 73rd, I encounter Calle. He is an Australian shepherd. He growls at me. I find this surprising since my relations with Fleur, a dachshund, and Spencer, an English Spaniel puppy – other dogs in the building – are excellent. The dog’s owner says that Calle may have thought I was planning to steal one of his sheep. Calle has a sixth sense, for I do think a lot about lamb chops, my favorite meat dish.

Many more young children now live in the building. They make the passenger elevator a lively gathering place. I believe I am the senior person, both in terms of age and tenancy, in the building. My age, and that of the children, span many decades, but we laugh at the same things.

Mother enjoyed using the fireplace in her living room on festive occasions. She purchased fire wood from Clark & Wilkins. When my classmates were boasting of jobs obtained in their final law school year with leading firms in the city – White & Case, Sullivan & Cromwell, Shearman & Sterling – I, who had yet to be hired by anyone, when asked where I would be working, would modestly lower my eyes and respond, Clark & Wilkins. To my ear, this sounded suitably law-like and Anglo-Saxon.

My fireplace has been a bit of a bust. The city’s Fire Marshals refuse to let us store wood in the basement. When I bring wood upstairs in jute bags to store in my apartment, it arrives with considerable insect life. I do not welcome these visitors. Now we have been told, no fireplace use by anyone until the chimney flues are fixed.

This summer has been a time of immense activity in the building. The installation of a new passenger elevator and freight elevator and a three month operation to replace crumbling bricks on the exterior walls. The building is wrapped in a scaffolding of steel pipe and wood. On weekdays, between 8 and 5:30, workmen troop past my sixth floor windows along a wooden platform. Privacy has vanished. This is followed by hugely loud drilling, like the drill of a mad dentist. An incentive for me to leap out of bed and make an early departure for the office.

The improvements are costing a lot of money. The owners of each cooperative apartment will be assessed for these expenses. I will not be assessed, since decades ago, I chose not to purchase the shares to my apartment. I live in what is termed a rent controlled apartment. The rent rises slowly, far below the market rate. Should I be ashamed of taking advantage of an ancient emergency rent law going back to World War II? Probably, but then I remember mother’s response to the same question: “Texans have their oil depletion allowance, I have rent control.” (Those who did purchase cooperative shares, of course, have been amply rewarded over the years.)

My favorite piece of furniture in the apartment is the living room couch. Here, stretched out, I listen to operas, read, watch basketball and soccer games, old films, news programs, imbibe a daily gin and tonic – Bombay gin, of course, with lime – and take delightful, refreshing naps. And if I am in a poetic mood, I think of the clouds passing overhead, having traveled West to East, completing their continent journey from sea to shining sea, and now bidding farewell to land and human habitation, bravely setting forth to encounter the vastness of the lonely sea.