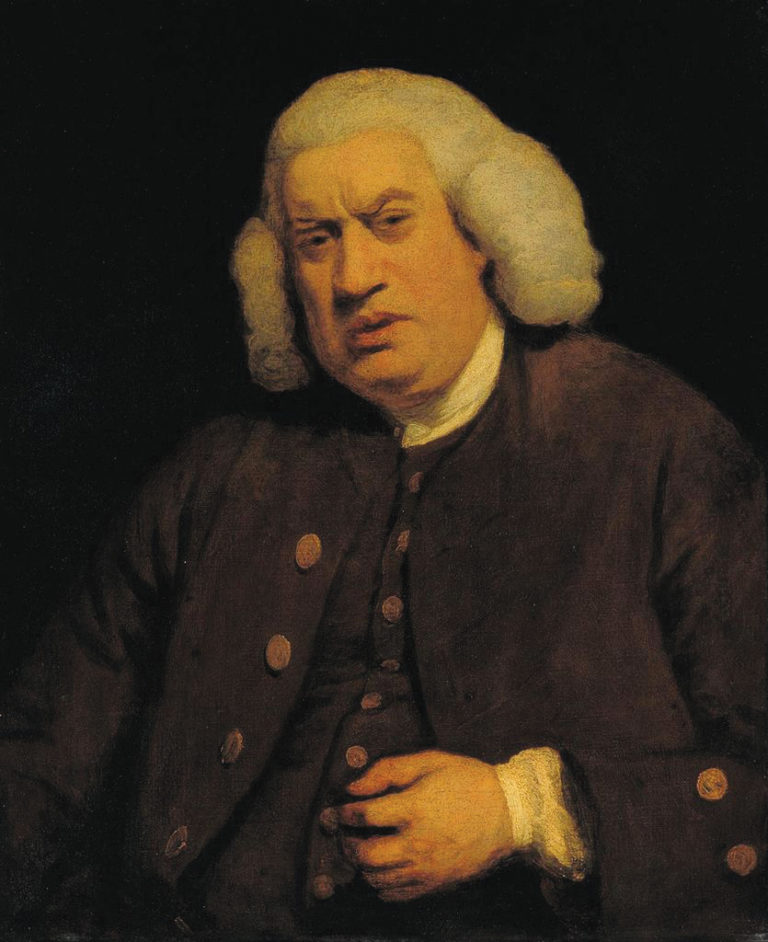

On June 18, 1746, Samuel Johnson, then age thirty-six, entered into a contract with seven London booksellers to write a dictionary. A book can be written in a room; dictionary-writing requires a house. Johnson rented 17 Gough Square, near Fleet Street. He chose the garret, with its high ceilings and numerous windows, as his workroom. He and Mrs Johnson occupied the lower floors. Next he hired six copyists.

Obtaining a workroom and hiring copyists is the easiest part of a dictionary writer’s job. How does one proceed from there? Do you include words like horse, dog, cat, words so common that nobody needs to look them up? Johnson decides to include them, for it is impossible to draw a line between the animals we know and those less well-known, such as crocodile, ichneumon and hyena.

How best to exemplify a word’s various shades of meaning? Johnson decides to select illustrations from works of literature, history, philosophy and science. Among English lexicographers he is a pioneer, for up to this point English dictionaries were more in the nature of word-lists, primarily concerned with giving the origin of words. Johnson was following the accepted practice among continental lexicographers, but with this important difference: In other countries entire academies of scholars undertook what Johnson attempted alone. (Boswell on Johnson: “a robust genius, born to grapple with whole libraries.”)

Which selections to include? Johnson: Those that “may give pleasure of instruction by conveying some elegance of language, or some precept of prudence or piety.” Here, as an example, he selects a quotation to illustrate the meaning of the word, “antedate”:

By reading, a man does, as it were,”antedate ”

his life, and makes himself contemporary with

ages past. (Jeremy Collier)

Should one cite living authors? Johnson avoids this except “when some performance of uncommon excellence excited my veneration, when my memory supplied me, from late books, with an example that was wanting, or when my heart, in the tenderness of friendship, solicited admission for a favourite name.”

When David Garrick, the actor and Johnson’s close friend, complains that the Dictionary cites present-day writers beneath the dignity of such a work, Johnson responds: “Nay, I have done worse than that; I have cited thee, David.” He cites Shakespeare more than any other writer and fixed Sir Philip Sidney (1554 – 1586) as the boundary beyond which he will make few excursions.

How to list words with more than one spelling? Johnson decides to list them twice — choak, choke / fewel, fuel / sope, soap — “that those who search for them under either form, may not search in vain.” Collecting words proved difficult. Johnson: “The deficiency of dictionaries was immediately apparent; and when they were exhausted, what was yet wanting must be sought by fortuitous and unguided excursions into books.” Surrounded by books, this true bookseller’s son reveled in his “feast of literature,” selecting words and quotations from the finest writers. “The books he used for this purpose,” writes his friend, Sir John Hawkins, “were what he had in his own collection, a copious but miserably ragged one, and all such as he could borrow; which later, if ever they came back to those that lent them, were so defaced as to be scarce worth owning.” In “Defining the World, The Extraordinary Story of Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary,” Henry Hitchens writes, the garret became “a sort of backstreet abattoir specializing in the evisceration of books.” While Johnson read in a corner of the garret, “tugging at his oar,” his copyists sought to carry out his instructions.

These were as follows, as described by Bishop Thomas Percy, a Johnson friend: To draw a line in pencil under each sentence he decides to quote, indicating in the margin the first letter of the word which the quotation illustrates. The marked book is then handed to a copyist who transcribes the quotations on single slips of paper and arranges them under the appropriate word. Later, Johnson writes definitions, determines spelling and pronunciations and inserts etymologies.

As month after month passed, Johnson became jaded. He compares his labor to those of the anvil and the mine: “a poet doomed at last to wake a lexicographer.” The Dictionary went so slowly that the booksellers threatened to cut off payments. The material he had already amassed was enough to frighten everyone away by its bulk. “Thus to the weariness of copying,” Johnson wrote, “I was condemned to add the vocation of expunging.”

And he had many personal worries. The health of his wife, now in her sixties, twenty years older than he, was undergoing a rapid decline. Her death in 1752 shattered him. At three in the morning he summoned a minister to 17 Gough Square. Together they prayed by the bedside of the dead “Tetty.” A few hours later, Johnson writes to the minister: “Let me have your Company and your Instruction. Do not live away from me. My Distress is great.” While he continued to live in Gough Square, he would study in no room, but the garret, “Because in that room only I never saw Mrs. Johnson.”

Johnson’s moods were erratic. Following a burst of activity, a severe bout of indolence accompanied by depression might take hold. When so afflicted, he could gaze at the town clock for hours and be unable to summon the necessary concentration to read the time.

The stereotype of Johnson is a curmudgeon delivering crushing retorts. Aggressive by nature, he certainly relished victory in verbal confrontations. Overlooked are his many acts of kindness. Scolded for giving coins to beggars who will only lay them out for gin, Johnson responds, “And why should they be denied such sweeteners of their existence?” His concern for the welfare of his copyists continued long after the Dictionary’s publication. To Shiels, often in financial distress, he sends money. He writes a preface to the elder Macbean’s geography book to help promote its sale, and finds him a place in a home for “decayed gentlemen.” He helps to arrange a theater benefit for Milton’s indigent granddaughter: “an opportunity…to secure the praise of paying a just regard to the illustrious dead, united with the pleasure of doing good for the living.” After Mrs. Johnson’s death, the Gough Square house becomes a haven for various destitute persons. He personally buys oysters for Hodge, his old and infirm cat, so that his servant “might not be hurt at seeing himself employed for the convenience of a quadruped.” Much of the time, Johnson is on the verge of financial ruin. A year after publication of the Dictionary, he is writing to his friend, the novelist, Samuel Richardson: “Sir, I am obliged to entreat your assistance. I am now under an arrest for five pounds eighteen shillings.”

Finally, Johnson could write, “I now begin to see land, after having wandered …in this vast sea of words.” He expresses “parental fondness” for his Dictionary. The title page of volume one remains open until the last possible moment in anticipation of Johnson being awarded a Master of Arts degree by Oxford. Johnson dares not tell friends of the possibility, “for fear of being laughed at for my disappointment.” How gratifying when it arrives. A quarter century earlier, unable to pay the fees, Johnson had been forced to discontinue his studies at Oxford. (He becomes Doctor Johnson with the awarding of an honorary Doctor of Laws in 1765 by Trinity College, Dublin.)

The Dictionary was published on April 15,1755. Issued in two volumes, it contains the definitions of 40,000 words with 114,000 quotations illustrating them, “drawn from the entire range of English writing, in every field of learning, from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth centuries,” writes Walter Jackson Bate in “The Achievement of Samuel Johnson.” (I had the privilege of taking the Johnson course of Professor Bate at Harvard College. When mother asked me to select a college graduation present, I requested this book.)

Johnson could take special pride in the completion of this mammoth undertaking. Elsewhere, he had written, “great works are performed, not by strength, but by perseverance.” Yet, as he well understood, a lexicographer’s work can never be completed. The words of a living language are in constant flux. “When they are not gaining strength, they are generally losing it. Though art may sometimes prolong their duration, it will rarely give them perpetuity; and then the changes will be almost always informing us that language is the work of man, a being from whom permanence and stability cannot be expected.”