The fortunate reader occasionally comes upon a book that “flings wide the gates of a new world.”The words are those of the French entomologist, Jean-Henri Fabre, his reaction to an essay he had just read on the habits of wasps. When reading a collection of Fabre’s insect studies, I experience the same sensation.

The son of peasants, Fabre was born in 1823 in Saint-Leons, a market town in the south of France.

From earliest childhood, he delighted in the company of beetles, bees and butterflies. He could find nothing in his background to explain this interest. Neither his careworn father nor illiterate mother was the source, and his maternal grandfather, a process server, “certainly paid no attention to the insect; at most, if he met it, he would crush it under foot.”

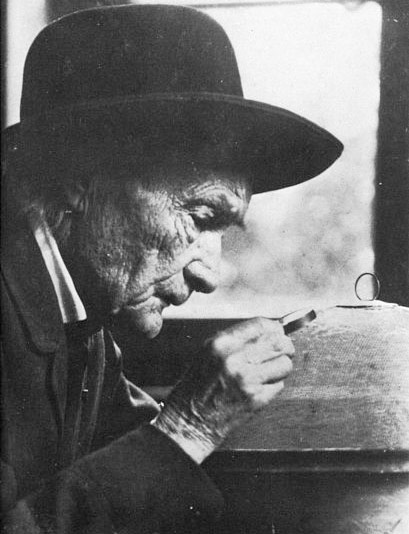

Fabre became a teacher and taught physics at the Lycee of Avignon for many years, using the summer holidays to pursue the study of insects. Like his father, he was harassed “by a terrible anxiety about one’s daily bread.” For many years he could not even afford a microscope, using a pocket lens in his work instead.

The Lycee dismissed him for admitting girls in his science class. He averted financial ruin only through the generous assistance of the English philosopher, John Stuart Mill, then living in Avignon, who provided him with a $600 loan. In 1879, at age 55, from income earned by his writings, Fabre was able to purchase a small plot of land near the town of Orange in Provence. Here he pursued his entomological studies until his death in 1915 at age 91.

Fabre regarded all forms of life with deep reverence. He addressed the subjects of his studies as intimates: “O my busy insects, enable me to add yet a few seemly pages to your history.” “Dear insects.” “O my pretty insects.” “My dear beasts.” “My old friends.”

Each insect is lovingly portrayed. The scarab beetle, for example: “He is smaller than a cherry-stone, but of an unutterable blue. The angels in paradise must wear dresses of that color.”

Fabre has unbounded enthusiasm for his work, always an appealing quality. He writes: “It seems to me so natural, so much within everybody’s scope, so absorbing to interest one’s self in everything that swarms around us.” By sunlight and lantern light he observes his friends in the fields. He enjoys the company of a wasp at dinner. He describes himself as a self-appointed inspector of spider webs. (Thoreau described himself as a “self-appointed inspector of snow-storms and rain-storms …surveyor, if not of highways, then of forest paths….”). When reading the works of the great entomologists, he resolves to himself, “You also shall be of their company!”

He possesses what Edwin Way Teale, the American naturalist and writer, describes as “that divine gift of all great teachers, the ability of transmitting his enthusiasm to others.” Fabre writes for men of learning, but, in his own words, “above all things for the young. I want to make them love natural history.”

He involves his sons in his work, noting proudly that one of them, Emile, has created in his upstairs room “a fence of dictionaries [which] encloses a park for the rearing of some caterpillars of the Spurge Hawkmoth.” (Another father and son shared a deep interest in butterflies: Vladimir Nabokov and his father. Prior to the Russian Revolution, the elder Nabokov began serving a prison sentence for publishing a revolutionary manifesto. He asks in a note sent from prison, “Did Vladimir get any ‘Egerias’ [Speckled Woods] this summer?” In an early poem, his son had written, “We are the caterpillars of angels.”)

Fabre realizes that many people consider him hopelessly eccentric. Far from taking offense, this amuses him. He relates that while engaged in field studies, he has been taken for a water-diviner, a searcher for buried treasure, a gypsy, a tramp and a poacher. One day, while observing the details of a fly household, suddenly he hears an official cry out, “In the name of the law, I arrest you.” Fabre tries to explain the situation. “Pooh!” the officer says. “Pooh! You will never make me believe that you came here and roast in the sun just to watch flies. I shall keep an eye on you, mark you!” Vine-pickers pass him in the field. One taps her forehead and whispers to another, “Un paoureinoucent, pecaire !” — “Look at this pitiful innocent!”

For the last 37 years of Fabre’s life, the 2.47 acres of barren, sun-scorched land in Provence he owns become his private Eden. Here he revels in the joys of “an earthly paradise for the Bees and Wasps.” In an unlovely patch of pebbles enclosed by four walls, he finds fulfillment.

His laboratory is that of the open fields. “I go the circuit of my enclosure over and over again, a hundred times, by short stages; I stop here and I stop there; patiently, I put questions and, at long intervals, I receive some scrap of a reply. The smallest insect village has become familiar to me: I know each fruit-ranch where the Praying Mantis perches; each bush where the pale Italian Cricket strums amid the calmness of the summer nights…each cluster of lilac worked by the Megachile, the leaf-cutter.”

He calls upon the insects to testify as to his industry. “Come here, one and all of you — you, the sting bearers, and you, the wing-cased armour-clads — take up my defense and bear witness in my favour. Tell of the intimate terms on which I live with you, of the patience with which I observe you, of the care with which I record your actions.”

The study of insects sustains him in his heaviest trials. In homage to his son Jules, who dies at the age of 15, Fabre concludes the first volume of his monumental work, “Souvenirs Entomologiques,” with these words:

I was to write this book for you, to whom its stories gave such delight; and you were to continue it one day. Alas, you went to a happier home, knowing nothing of the book but its first lines! May your name at least figure in it, borne by some of those industrious and beautiful Wasps whom you loved well!

Reading Fabre, one comes to revere the beauty and mystery of every living thing. His work is an affirmation of life — hugely appealing in our troubled times

The Field Cricket

In your company …O my Cricket, I feel the throbbing of life, which is the soul of our lump of clay; and that is why, under my rosemary-hedge, I give but an absent glance at the constellation of the Swan and devote all my attention to your serenade! A living speck–the merest dab of life–capable of pleasure and pain is far more interesting to me than all the immensities of mere matter.

–Jean-Henri Fabre,“Souvenirs Entomologiques”