Two deep interests of mine are opera and prisons. With Beethoven’s opera, “Fidelio,” these interests converge. As the crystal chandeliers rise to the ceiling, and then dim, the curtain opens on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City for an evening performance of “Fidelio,” Beethoven’s only opera. An audience of 2500 is in attendance. The stage setting: A prison outside Seville in 18th century Spain. Cells are seen with barred windows and iron doors shuttered with steel bolts. In the background, a high wall looms. The world of high walls and locked cells, along with more recent prison paraphernalia, such as towers with powerful searchlights and armed guards, and fences topped with gleaming razor wire, are familiar to me as a visitor to prisons over the years.

“Fidelio” is an opera that moves from human suffering — life in prison — to deliverance, with the triumph of justice. (In real life, this desirable progression does not always occur.) The heroine of the story is Leonora, wife of Florestan. He is a political prisoner in chains in the prison dungeon. She arrives disguised as Fidelio, a young man looking to work in the prison. Her real purpose is to find and save her husband and expose the misdeeds of Pizarro, the villainous governor of the prison.

In November, 1805, in Vienna, at age 34, Beethoven had to deal with on-coming deafness and the usual problems in bringing a new work to the stage — musicians “murdering my music.” In addition, Austrian censors objected to references in the libretto to “freedom” and “equality”. And then the French chose this time to arrive as an invading force, with 15,000 troops marching into Vienna. Jan Swafford writes in his splendid biography, “Beethoven, Anguish and Triumph,” the “circumstances of launching a serious and ambitious opera … high in ideals could hardly have been worse.”

The small audience attending the opera was made up mainly of French officers, the Austrian emperor and his court having fled the city, leaving Napoleon comfortably ensconced in the Schonbrunn Palace. Beethoven presided at the pianoforte and directed each performance. There were only three. A rocky start for an opera later to be acclaimed a masterpiece.

In “Fidelio,” the jailor, Rocco, comments, “Hard is the jailor’s gloomy task.” Life in prison continues to be hard, for both keepers and kept. Bars produce a deep sense of claustrophobia. Today’s cells are not the dungeons of “Fidelio,” but they are grim. A bed, sink, toilet. Little or no natural light. Wash hanging from lines strung from wall to wall in the cell. Some cell blocks are a city-block long. Prisoners in cells stand by the bars to gaze out onto the corridor, or lie on beds, staring at the ceiling. Some read. Moving from cell to cell, I ask, “How long have you been in prison?” The response may be ten or twenty or thirty years, or even more. What wasted lives. From outside the prison, the sound of a train whistle. Freedom seems light years away.

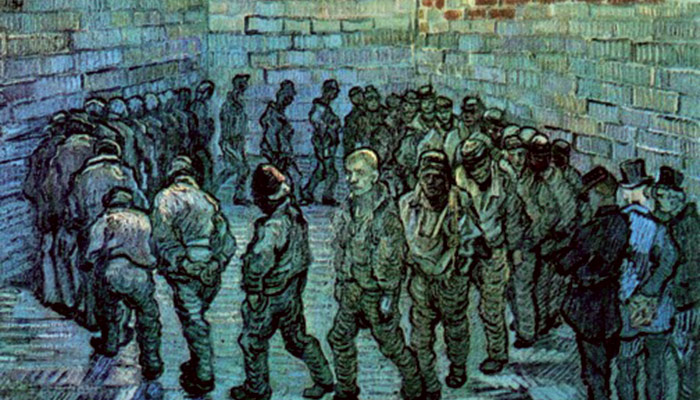

Acts of kindness occur in “Fidelio,” as they do in prisons. On my visits, I meet caring correction officers and program staff. In the opera, Rocco releases prisoners from their cells to walk in the castle garden. Joyfully, the prisoners emerge from their dark cells into the sunlight. In prison, it is important not to lose hope, for the loss of hope leads to despair. Leonora realizes the need to avoid despair: “Sweet hope, oh never let your star, / Your last faint star of comfort be denied me.” The prisoners in their dungeons do their best to cling to hope: “The voice of hope still whispers here ….”

Hope is nurtured when a prisoner has loved ones on the outside who care about him. It is Leonora’s devotion that sustains her imprisoned husband: “By your love,” Florestan tells her, “I was protected.” I watch inmates waiting for visitors and see the warm smile of recognition when they arrive, “No, my family has not given up on me. I may be jobless, without a future, but still I have something.” An embrace. Hand in hand, family and friends begin their precious hour together.

Release from prison is the hope of every prisoner. In “Fidelio,” the prisoners ask, “Oh freedom, will you be ours once again?” Florestan is freed to the sound of trumpets with the arrival of Don Fernando, the king’s minister. No trumpet of deliverance will sound for the inmates I meet. In my view, many of them should not be in prison at all, not because they are innocent, but because less harsh punishments, such as remaining in the community subject to electronic monitoring, is far less destructive of family life than being sent many hundreds of miles away from home.

In the United States, we have 2.3 million adults in our prisons and jails. The sentences we impose are far too long. In the Federal system, there are mandatory minimums of 10 to 20 years for low-level drug crimes. If a prison term is imposed, let us embrace this opportunity to provide education for the undereducated, job training for the jobless, and care for the addicted and those with other medical and mental health needs. Some such programs exist, but they are underfunded, with long waiting periods to enter, resulting in idleness and wasted opportunities.

Years ago I came upon these two passages that convey immense wisdom. How different our prisons could be in the future if we should embrace them:

We Will Turn This

Prison from a Scrap

Heap into a Repair Shop.

(Thomas Mott Osborne,

American Prison Reformer)

Remember all prisoners…and

give them hope for the future….

Remember those who work in these

institutions; keep them humane and

compassionate; and save them from

becoming brutal or callous.

(Book of Common Prayer)

“Fidelio” is in the spirit of both passages. The kindness of Rocco and the wisdom of Don Fernando, who speaks to the prisoners:

No tyrant here you’ll find in me.

A brother comes to seek his brothers,

If he can help, he gladly will.

The prisoners respond to his caring words:

Here clemency unites with justice….

May all prisoners, like those in “Fidelio,” find peace.

* * *

“Though this life promised him nothing that the people of this great town called good and struggled to acquire: neither apartment, property, social success nor money, there were other joys, sufficient in themselves, which he had not forgotten how to value: the right to move about without waiting for an order; the right to be alone; the right to gaze at stars that were not blinded by prison-camp searchlights….Yes, there were many, many more rights like these.” – Alexander Solzhenitsyn,“Cancer Ward”