The 1960s Mosfilm’s production of Tolstoy’s, “Warand Peace,” running seven-plus hours and shown in four parts, directed by Sergei Bondarchuk, arrived in New York City this past February for a limited number of viewings. I fight like a tiger to purchase four tickets at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater, managing to obtain only three and not even in the right order: Parts 2,1 and 3, and no part 4 at all – Moscow aflame, to save the city from Napoleon – having been sold out. But no complaint from me. To be present at any part of this brilliant film with Pierre, Natasha, Andre, and his father, the dreadful Prince Bolkonsky, each wonderfully portrayed, and to watch in awe the 15,000 extras loaned to the production by the Soviet Army to reenact the Battle of Borodino, was a thrilling experience.

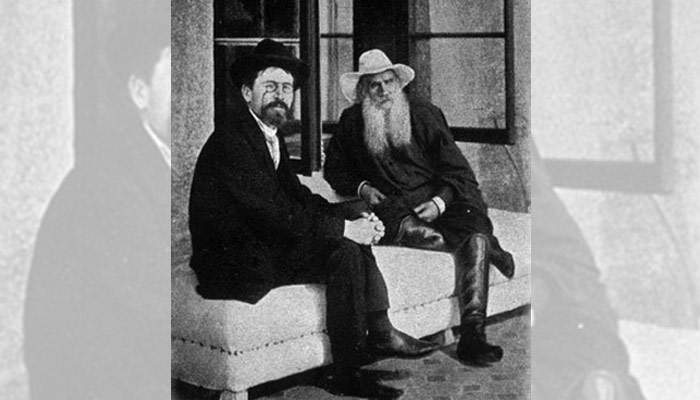

Why such passion on my part to see the film? Though I bear the name, William Johnson Dean, father having been born in the Southern state of Kentucky, my mother was born in Russia. This places me under a genetic obligation to attend the film. And even stronger ties demanded my appearance. My Russian grandfather, Alexander Micheles, came to spend time with Tolstoy when serving as managing director of a major gramophone company based in Moscow. Grandfather had the idea to record the voices of well-known Russian writers and turn the profits over to a charity for the benefit of impecunious members. And what an excellent advertisement for the company’s gramophone this would be.

Grandfather began with the writers Andreyev, Kuprinand Bunin, but being ambitious, made plans to record Tolstoy. In 1909, Tolstoy was eighty-one years old. Though old fashioned and suspicious of “progress,” Tolstoy could not resist the fascination of inventions, such as the cinema and mechanical piano. He would walk to the entrance of his estate and take pleasure in watching bicycles and automobiles pass on the road. Perhaps the talking machine would excite Tolstoy’s curiosity.

The “peasant writer,” Semyon Terentlevich Semyonov, a close friend of Tolstoy, served as the emissary for grandfather’s group. The response from a Tolstoy daughter was not encouraging: “he has recently been feeling so weak that it would be difficult for him to speak into a phonograph….” Semyonov decided prompt action was necessary and went to Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy’s country estate, 200 miles south of Moscow, where he had been born. Entry from Tolstoy’s journal: “Semyonov arrived today and assured me that I couldn’t refuse the phonograph.” Semyonov to his fellow conspirators: “Get ready, you are expected. Lev Nikolayevich has agreed, he feels energetic and yesterday went horseback riding.”

Soon thereafter, on October 17, 1909, Grandfather arrived in the evening by train from Moscow with his colleagues: Semyonov, a recording engineer, journalist, photographer and poet. From the station they proceeded by carriages to Yasnaya Polyana. The journalist asks a carriage driver, “Do you know Lev Nikolayevich?” The driver responds, “We are constantly taking guests to him. He’s an ordinary muzhik [Russian peasant] but according to the papers he’s actually a great man.”

At Yasnaya Polyana they find Tolstoy writing. He is dressed in a warm knitted shirt. A shaded kerosene lamp on the desk provides light. Tea is offered the guests. Grandfather converses with Tolstoy in French, Russian and English. At 11:30, Tolstoy wishes his guests a good night, kisses his wife, Sophie Andreevna, and retires. She has beds prepared in the library for grandfather and a colleague.

Tolstoy rose at seven and took a long walk with his small dogs. Grandfather joined him on some of his walks. A photograph of Tolstoy was taken under the “tree of the poor” where he received petitioning peasants. In the library, Tolstoy selected readings for recording. When reading, he carefully enunciated each word. Among his readings, “Do not be anxious that you be loved. Love and you shall be loved.” // “It is neither shameful nor harmful not to know, but it is shameful and harmful to pretend that you know what you do not know.”

Grandfather requested that Tolstoy read in Russian, French and English. The engineer asked him also to do so in German. Then Tolstoy said, “I’m tired now.” Coffee and home-made bread were served in the dining room. Grandfather presented Tolstoy with a company gramophone. Tolstoy presented his guests with autographed portraits. Tolstoy gave grandfather a book on which he had inscribed these lines:

“Give the people wholesome entertainment.” “Give them the ideas and counsel of good writers presented on your records in popular form. Your record will be as beneficial as a book.”

Tolstoy’s lines were so appropriate to the occasion, as they are today.

Mother visited Yasnaya Polyana decades later. In 1973, my third generation visit seemed doomed when in Moscow I learned the house would be closed the one day I could visit. I told a sympathetic Intourist representative about grandfather. To my immense delight, she arranged to have the house opened for a visit by me. My Moscow guide and I had Yasnaya Polyana to ourselves in the company of a Tolstoy expert on the staff.

It rained steadily during the 3 1/2 hour drive from Moscow. As I walked past the two sentinel towers of whitewashed brick at the entrance to the estate, and along the narrow, tree-lined avenue leading to the house, the weather cleared. The sky was as at Austerlitz in “War and Peace” when Prince Andre falls wounded – “not clear, yet still immeasurably lofty, with gray clouds gliding slowly across it.”

The young Tolstoy was no ascetic. To cover his gambling debts, he sent instructions from the Crimea battlefront to his brother-in-law to sell the big family house on the estate, but not the land. In 1854 the house was dismantled board by board and carted away. All that remained were two pavilions which formerly flanked the mansion house. Wings were added to these pavilions as the Tolstoy family grew.

The furnishings are modest. The dining room table was set as it would have been in Tolstoy’s day, with small pots for vegetables in front of his place. Late in life he became a vegetarian.

Grandfather described the food as very plain. Close by, in the same room, is a small table with a lamp. Following dinner, family and guests would gather around the table to hear Tolstoy read passages from his most recent work. In the study are the couch where he was born, his writing desk and the table where Sophia Andreevna painstakingly made clean copies of his endlessly revised manuscripts. To my enormous delight, I come upon the talking machine presented by grandfather to Tolstoy. Mother had seen the gramophone on her visit.

I travel the path Tolstoy followed when he fled at dawn from Yasnaya Polyana in 1910 – from his bedroom, to his study, where he wrote Sophia Andreevna a farewell note, and then to the carriage house. He believed that flight alone would enable him to live in accord with the principles of simplicity he espoused. Eleven days later, on November 20, 1910, at age 82, hundreds of miles from Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy’s flight and life ended in the home of a train station master. Grandfather’s stay with Tolstoy had been only 13 months earlier.

A gentle rain falls, called “a mushroom rain” in Russia. From the carriage house I walk to Tolstoy’s grave. His burial place lies in a birch wood, on the edge of a ravine in Zakaz forest, about a quarter of a mile from the main house. There is no monument, only a mound of earth. The simplicity is breathtaking. Tolstoy left detailed instructions as to where he wished to be buried. At age five, relates his biographer, Henri Troyat, his brother, Nicholas, told him a story of a secret so powerful that when it became known, sickness would vanish from the earth and love would flower in every heart. Nicholas said the secret was carved on a green stick, and the green stick lay buried in the Zakaz forest.

The story made a profound impression on Tolstoy. Late in life, he wrote: “I used to believe that there was a green stick on which words were carved that would destroy all the evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good, and I still believe today that there is such a truth, that it will be revealed to men, and will fulfill its promise.”

Having been unable in a lifelong search to find the green stick, Tolstoy chose to be buried near it.