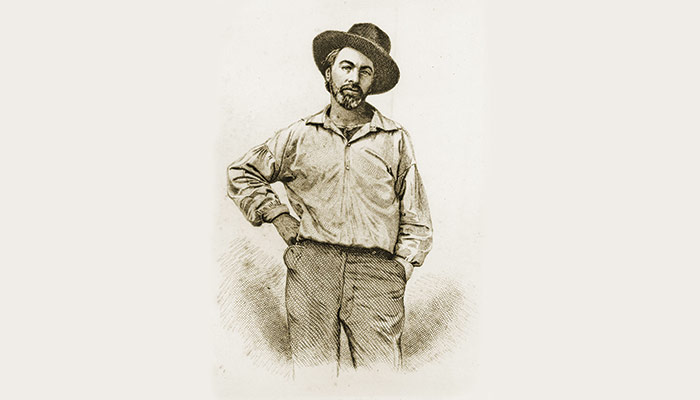

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Walt Whitman (1819-1892). He is a favorite poet of mine. Why? A shared love of place; indeed, of the same place: New York City. His poetic voice: the energy, emotional intensity, enthusiasm, joy. His spirit of personal independence.

Justin Kaplan, in his biography, “Walt Whitman, A Life,” writes that “America’s first urban poet began as a student of the city’s rhythms and sounds.” In 1830, at age eleven, Whitman’s formal studies ended and he started work as an office boy in a law firm, delivering legal papers and exploring the two cities along the East River: New York and Brooklyn. As a newspaperman and poet, Whitman came to know his two cities well: “Brooklyn of ample hills, was mine, / I too walk’d the streets of Manhattan Island….”

Whitman enjoyed riding the Broadway omnibus and would help the drivers collect fares. On the omnibus, or on the East River boats plying between Brooklyn and New York, Whitman sometimes would declaim Homer and Shakespeare, or sing snatches from opera. He loved the opera and believed that without the emotional intensity it provided him, he might never have become a poet.

The harbor was a favorite part of the city for Whitman. The first time he ever wanted to write anything enduring was “when I saw a ship under full sail, and had the desire to describe it exactly as it seemed to me.” And describe ships he did. “Look’d toward the lower bay to notice the vessels arriving,…/ Saw the white sails of schooners and sloops, saw the ships at anchor,/ The sailors at work on the rigging or out astride the spars,/ The round masts, the swinging motion of the hulls, the slender serpentine pennants….”

As Whitman traveled by foot, omnibus and ferry, he became increasingly aware of the beauty of his two island cities. “The glories strung like beads on my smallest sights and hearings, on the walk in the street and the passage over the river.” Whitman was inspired by his city. Of his masterpiece, “Leaves of Grass,” he wrote, “Remember, the book arose out of my life in Brooklyn and New York…absorbing a million people …with an intimacy, an eagerness, an abandon, probably never equaled.”

Passages from Whitman:

— Mannahatta! How fit a name for America’s great

democratic island city ! The word itself, how

beautiful! How aboriginal! How it seems to rise

with tall spires, glistening in sunshine, with such

New World atmosphere, vista and action!

— City of the world! (for all races are here;

All the lands of the earth make contributions here;)

— City of the sea! City of hurried and

glittering tides!

— A hundred years hence, or ever so many

hundred years hence, others will see them.

Will enjoy the sunset, the pouring in of the

flood-tide, the falling back to the sea

of the ebb-tide.

In the streets of New York, Whitman was a witness to history. “When a great event happens, or the news of some great solemn thing spreads out among the people, it is curious to go forth and wander a while in the public ways.”

By City Hall in downtown Manhattan, Whitman watched President-elect Abraham Lincoln arrive at the Astor House, the city’s most elegant hotel. “I had…a capital view of it all, and especially of Mr. Lincoln, his look and gait – his perfect composure and coolness – his unusual and uncouth height, his dress of complete black, stovepipe hat push’d back on the head, dark-brown complexion, seam’d and wrinkled yet canny-looking face ….”

Whitman learned of the April 13, 1861 bombardment of Fort Sumter by rebel forces marking the start of the American Civil War as he walked down Broadway to the ferry to return home to Brooklyn after attending a performance of Verdi’s opera, “A Masked Ball.” Newsboys were selling papers announcing the event. He bought a copy and read it under a gas street lamp.

Four years later he shared the excitement and profound relief of his fellow New Yorkers when word reached the city of the meeting at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia of Generals Grant and Lee, bringing the Civil War to a close. A savage war, with an estimated death toll of 620,000. Church bells tolled six days later, this time for the slain president. Jubilant banners along Broadway were replaced by weepers of black muslin. As Whitman strode along Broadway that day, he wrote in his notebook: “Black clouds driving overhead. Lincoln’s death – black, black, black – as you look toward the sky – long broad black like the great serpents.” Months later he was to write his elegy on Lincoln. The poem’s opening lines:

When lilacs last in the door-yard bloom’d,

And the great star early droop’d in the western sky

in the night,

I mourned … and yet shall mourn with ever

returning spring.

Years earlier, in 1855, Ralph Waldo Emerson had received an unsolicited copy of “Leaves of Grass” from Whitman. This was the book Emerson had been yearning for – the work of a powerful poet with an authentic American voice. Emerson sent to Whitman what has been described as the most famous communication from one writer to another in American literary history: “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit & wisdom that America has yet contributed….I greet you at the beginning of your great career….”

A breathtaking endorsement by a towering figure of American letters to a person deemed by some to be an outcast, Emily Dickinson among them. Of “Leaves of Grass,” she wrote, “You speak of Mr. Whitman – I never read his book – but was told he was disgraceful.” Lines of his like these shocked readers: “I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world!” “Camerado, this is no book, who so touches this touches a man.” An alert from Whitman that what lay ahead on the pages of his work would be a new literary landscape.

Whitman was fiercely independent when it came to his poetry and life style. He wrote of himself: “I had my choice when I commenc’d. I bid neither for soft eulogies, big money returns, nor the approbation of existing schools and conventions….I have had my say entirely my own way…..”

He did, indeed. We are forever the beneficiaries for his having done so.