At this time of year in frigid New York – a temperature of 5 degrees is predicted for tomorrow — I think a lot about Prometheus. A Titan in Greek mythology, Prometheus stole fire from Zeus for the benefit of mankind, bringing warmth to shivering humanity. We all are indebted to him, even those living in warm climates like India. Because of Prometheus, heat emanates from radiators at home and office and fire is available for cooking and boiling water.

For stealing fire from Zeus, Prometheus was made to suffer most cruelly, being chained to a rock on Mount Caucasus. Here, during daylight, an eagle dispatched by Zeus, nibbled away at his liver. His liver was fully restored at night. The cycle of torture resumed the next day and only ended when Zeus had his son, Heracles, kill the eagle, not to relieve Prometheus of his suffering, but in the belief that Heracles would enhance the family reputation by achieving immortal fame for doing so.

On very cold mornings in New York City, I wear my warmest suit, a heavy sweater, long wool scarf, knitted gloves and an old but warm winter coat. For headgear I put aside my elegant Borsolino and wear a black knitted cap to keep my ears warm. (Marlon Brando wore a similar cap when playing a rough-tough longshoreman in the movie, “On the Waterfront.”)

In New York, we are walkers, whatever the weather. (In summer, on the hottest days, the tar on the roadway is softened by the heat.) I am now ready to join fellow residents on the city’s streets. They, too, have abandoned elegant outerwear for warm clothing gathered from the deepest recesses of apartment closets. With faces partially concealed by scarves to ward off Arctic winds, we resemble wandering bands of desperadoes. “Stand and deliver!” I expect to hear from a passerby.

Athleticism is useful, broad- jumping in particular, as I leap from curb to roadway, and vice versa, when crossing slush-filled streets. If I am taking the subway to work, by the time I reach the station, even with gloves, my fingers are numb. I stand on the frigid platform. The subway arrives, the doors open, and I enter the car. I welcome the warmth of the interior with a broad smile. Bless you, Prometheus!

I survey the bundled-up passengers in their winter clothing. Many are from the Caribbean. As the subway speeds underground through cold dark tunnels, they may recall with heavy hearts scenes from earlier in their lives; perhaps palm trees swaying gently under a tropical sun.

If I am taking the bus to work, I welcome with equal fervor the warmth when boarding the bus on East 71st Street, having endured winter blasts sweeping across expanses of Central Park to reach the bus stop. The bus proceeds downtown. We pass the statue of Atlas, across the street from St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Atlas, like his brother, Prometheus, incurred the wrath of Zeus, having made war, along with the other Titans, upon Zeus. Atlas is condemned to bear the earth upon his shoulders. My mother’s professional work, being centered on the troubled field of international relations, led her friends, with affection, to call her, “Mrs. Atlas.” As the bus passes Atlas, I lower my head in tribute to Mrs. Atlas.

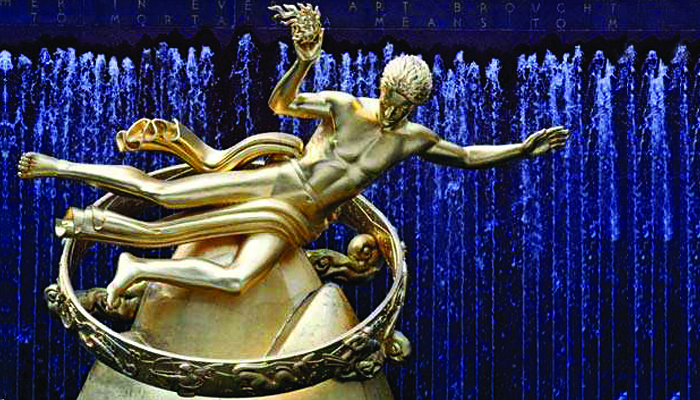

The eight ton gilded bronze figure of Prometheus, designed by Paul Manship, is a block away and visible from the bus. It is placed on a pedestal shaped like a mountain peak. On the wall nearby appear these words of Aeschylus, playwright of Ancient Greece: “Prometheus, teacher in every art, brought the fire that hath proved to mortals a means to mighty ends.”

Mr. Manship chose to forego the blood and gore associated with the eagle’s activity. Instead, Prometheus is depicted as a handsome and energetic youth ready and able to serve mankind. From my bus seat, I lower my head a second time in tribute.

I spend far more time walking than riding on buses. The city’s streets inform and entertain. It’s hard to be lonely in a place with so much human activity. I take practical walks — on errands — and pleasure walks through Central Park and nostalgic walks from 106th Street and Fifth Avenue, where I was born, to 96th Street on the Upper East Side where I grew up, to 73rd Street where I have lived since 1964. Much of my life has been spent within the confines of these blocks.

In the early morning, the sidewalks in my neighborhood are crowded with children and adults rushing to school and office. By 8:15, depending on the season of the year, the sidewalks are bathed in sunlight. Unlike Londoners and Parisians, New Yorkers are fortunate to have sunlight through much of the year, New York being on the same latitude as Madrid.

Outside my apartment building, I see a husky that looks newly arrived from the Artic, a poodle and an English bulldog. Dogs in the street come in many different sizes, shapes and colors, just like New Yorkers.

When taking the subway to work, I choose from among four world-class routes: south along Park, Madison or Fifth Avenues, or through Central Park. What vision the city’s leaders had when they created man-made Central Park, starting in 1857. In the spring and summer, “so fresh and charming the grass, the blossoms and flowers.” (Good Friday morning, as described in Wagner’s opera, “Parsifal.”) At Easter, cherry trees and daffodils in full bloom. Following the fallen leaves of autumn, snow. The city is at its quietest and most beautiful after a snowfall.

From the park I see the Frick Mansion. Behind French windows hang Mr. Frick’s collection of paintings: the sun-lit Umbrian hills of Giovanni Bellini. The London of Gainsborough and Turner. The Netherlands of Rembrandt, Hals, Vermeer.

In the zoo, I watch three sea lions savor their breakfast of raw fish as they glide through the water.

I pass the old pony track, long since shut-down, where as children my sister and I would be taken for rides. In Grand Army Plaza, carriage horses munch oats from feed bags.

At the subway entrance at 60th Street and Fifth Avenue, I descend steps to reach the track. On the tile walls of the station are depicted a family of playful monkeys and flock of high-flying birds. To me, they represent New Yorkers on the move, bursting with energy, ready to begin the new day. But if truth be told, in the morning I identify more with other tile figures: Seven turtles and a family of snails.

In the evening, when my imagination slips into high gear, I encounter the wheezing sound of Fafner, the dragon from Wagner’s “The Ring of the Nibelungen.” Fafner turns out to be an earth mover working on the Second Avenue roadbed.

Life in New York City, real or imagined, is always lively.